Understanding the photographic. More than ever, the musée Nicéphore Niépce continues to affirm its position as an all-purpose photography museum. It promotes photography as a whole that, since Niépce’s initial foray, cannot be reduced to just art and technique, or to the blend of the two disciplines. The choices are partial, this is not an exhaustive show, but one that emphasises the educational link between the photographic object and the spectator.

“Tous azimuts” (In all directions) presents recent and heretofore unseen acquisitions. The pieces include both purchases and donations and are a timely reminder of the museum’s vocation to assemble, conserve and show photography.

As a multi-faceted, ever-changing object, photography can be shown on walls, in books and magazines. It is freely exposed in family albums. To perceive photography in its coherent state and attempt to rebuild a photographic archive in its totality means going back to the way it links to our obsessions, our desires and our perversities; at the risk of putting the staggering panorama of humanity’s fascination for the medium on display.

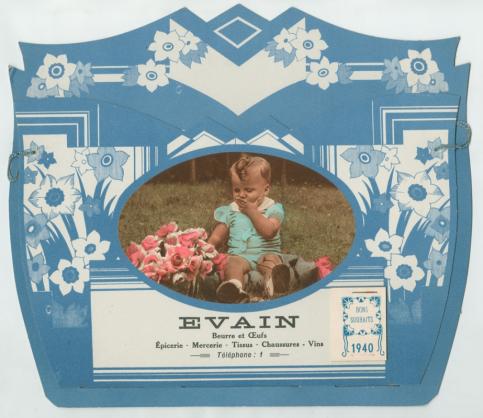

An advertising object

From the end of the 19th century, the demonstration power of the photography made of it an advertising object. But it was especially between the two wars that the photography was able to exceed the former advertisement based on text and drawing. Praising a product’s advantages, a brand or a commercial chain, it displayed on every kind of medium: poster, catalog, calendar, letter holder… The image’s impact is instantaneous. This one is supposed to prove the veracity of the message. At this time, the advertising image got back and was inspired by the avant-garde’s plastic experiments: photomontages, use of typography and color. Besides, it’s not harmless to note that the greatest photographers worked for advertising market.

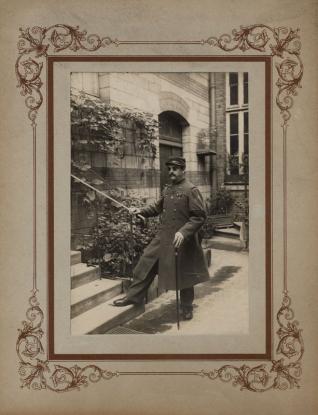

Photography in wartime

Photography in wartime is a multi-faceted genre. Its principal characteristic since 1914 has been, above all, the way it has been controlled to be used in the press as propaganda. Images were often retouched, scenes reconstituted after the fact. Photography became a weapon of persuasion to reassure the population (showing nothing) and to terrorise the enemy (showing them decimated). Totalitarian regimes added the cult of leadership to the mix by flooding conquered territories with thousands of solemn and intimating portraits. Then there were the souvenir photographs taken by soldiers that were, at times, very supervised.

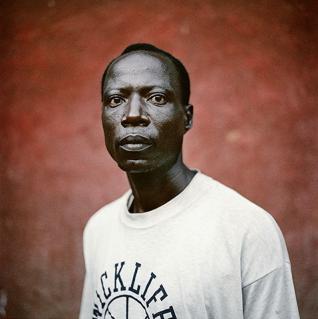

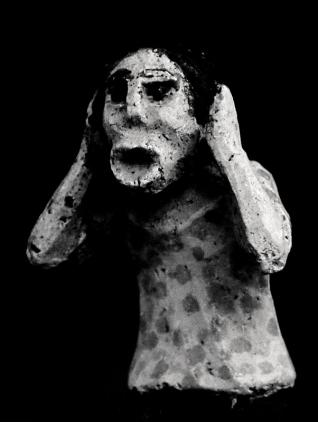

The mission of photo-reportage from the thirties onwards was to show what was going on in the wings, that which was hidden, to incarnate the conscience, to contribute to changing things – in vain. The representation of horror has never prevented it from existing. This horror can only be evoked through metaphor, transposition, like the way Laurence Leblanc takes close-up shots in modelling clay of the characters in a Rithy Panh film in the Khmer genocide. Or how Alexis Cordesse gathered testimonies from ex torturers from the Rwandan genocide that he put together with their intentionally banal portraits. The image does not work as immediate proof, it is instead a testimonial. The effect is no less forceful, it is amplified.

Identify

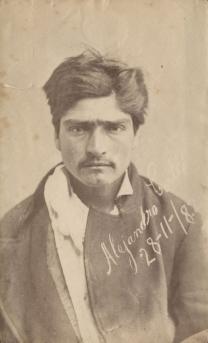

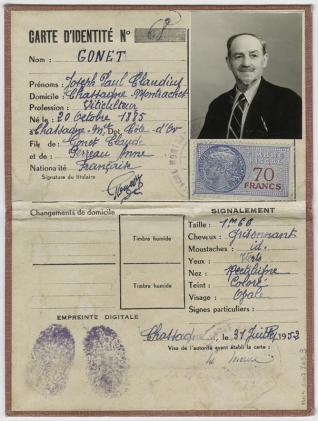

Photography quantifies and measures; it allows us to recognise, to identify. Thus, at the end of the 19th century it became a precious tool for police. Mug shots began to appear in criminal files and the first wanted posters to tackle the problem of re-offenders. Bertillon set up the first anthropometric database that used pictures and different measurements of the human body. The method was applied to increasingly broader swathes of the population, stigmatised as dangerous or potentially threatening: anarchists, nomads, political opponents, especially in the colonies… In France, the first identity cards with photographs were created in the 1890s. Identity cards for foreigners, French people, civil servants, exit and transit visas, residency permits, Ausweis under the Occupation… the administration counts, categorises, investigates, supervises.

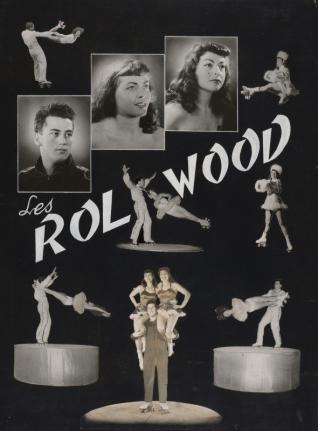

Thirties

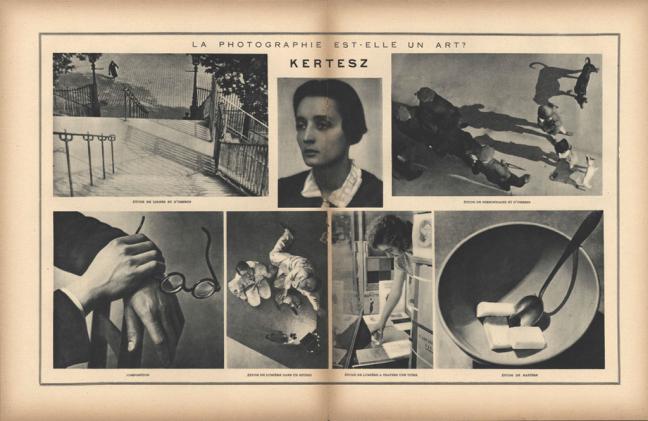

In the early thirties, photography became more experimental. It brought a broader repertoire of shapes and scenes to modernity, with new and founding attitudes. According to the artistic, social and political evolution of the time towards global transformation, photography’s “Nouvelle Vision” envisaged the visible through the geometry of bodies, factory materials and the beauty of the machine. In describing modern bodies, in photographing revolutionary architecture, in the scenography of a portrait, the photographer removed all that was superfluous from the frame. Today, we can only stand back and admire the common oeuvre of the “New Vision”, that owes everything to German and Hungarian immigrants, to the banished, the Jews, women and communists who made French and Parisian photography the melting pot for the renewal of the medium.

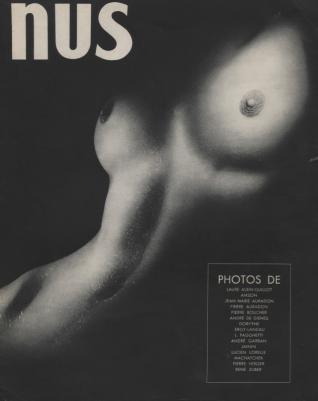

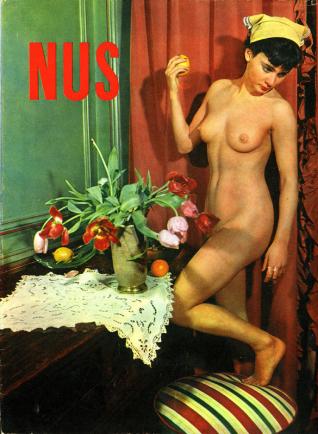

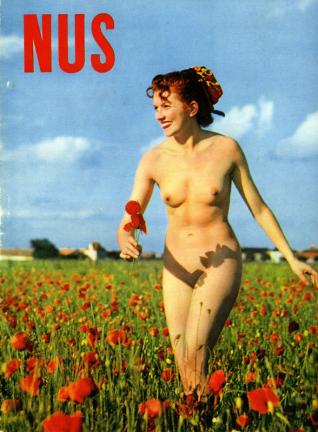

Nude

In the 19th century, photography perpetuated the tradition of the artistic nude as practiced in the fine arts. The body was treated as a study, an academic notion. While modesty remained the norm, and despite censorship, this did not prevent the proliferation of erotic images that made the nude photography’s first source of income. As early as the twenties, photographers highlighted the aesthetic qualities of the nude, in tandem with the widespread movement of liberation for the body in general. It was generally shot close-up, fragmented, starkly; it became a pure, aesthetic object sculpted by the light. In parallel, a type of erotic and kitsch photography continued to circulate under the table (Horace Roye). Today, free from censorship, photography has dispensed with traditional criteria of beauty and place the body, face and sexual organs in the same shot.

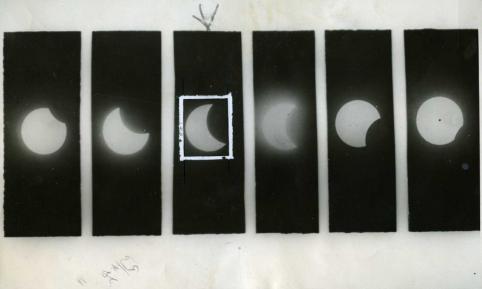

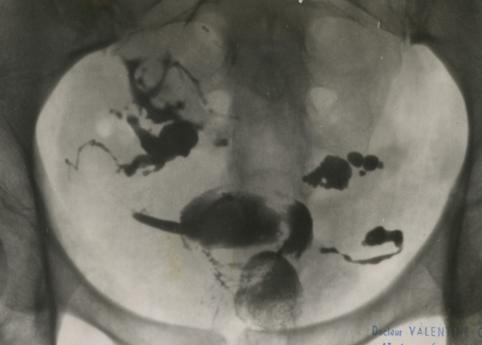

See beyond

The technical precision of photography that was boasted about from the very start, allowed the world to see beyond its field of perception. The photographic plate offered a huge range of detection: every tiny point of light could be captured as long as the brightness levels were high enough and the length of time sufficient. This is how photography certified the existence of some stars that had heretofore only existed on a page through mathematical calculations. It was also with a photographic plate that Röntgen revealed X rays in 1895. Photography allowed precise observation, the accumulation of details could be studied and identified making it useful to scientific progress. Many medical disciplines took it over such as psychiatry. Photography became the instrument that was essential to demonstration. Taking things further and affirming that it provides proof was but a step away, a step taken by certain unscrupulous “spirits”…

Publishing

Publishing brought photography to another level. From the illustrative in early 20th century newspapers, it led to the implosion of the traditional magazine just after the First World War, making photography the main player in modernity. The photographer became a reporter. The world was from then on seen with a subjective eye. Roto-engraving was to change everything and emancipate the image from the text. Every week, the reader got not only an illustration of the world, but the world itself. The image was no longer alone, it became part of a series. The double page grabbed the reader’s eye. Visual culture was born. These magazines provided visibility for photographers and their first critiques.

Current photographic art

The museum’s support for current photographic art takes various forms: acquisitions from photographers and galleries, grants to support projects or our artist in residence programme. The latter enables a photographer to conceive and produce an artistic project with the added advantage of the experience and availability of the museum’s photographic lab. This has meant that Virginie Marnat-Lempoels got a chance to explore female stereotypes at her leisure, such as the rich American lady surrounded by a décor that tells so much of her social origins. On the other end of the scale, Jake Verzosa did a series of portraits of the last tattooed women of the Kalinga tribe in the Philippines. Marion Gronier attempted to capture the feeling of abandonment of circus artists who go from the lights of the ring to the anonymity of their temporary dressing rooms. Stan Guigui depicted the misery and violence of El Cartucho, Bogota’s cour des miracles and joined the Mariachi community for a time… Photography is universal and the points of view on show here are multiple.

André Mérian : Water Front

As part of a commission for the “Marseille Provence European Capital of Culture », André Mérian photographed the ports of the Mediterranean, questioning unscrupulous urban sprawl, the result of property speculation. It is far from banal when for the first time in the history of geology, such huge transformations have been carried out to the structure of the landscape. For a photographer who choses to represent real landscapes, there is more sadness in depicting this world than in praising the beauty of the view. In the tradition of Marville or Atget, he records the passage from one world to another, showing us the end of a myth.