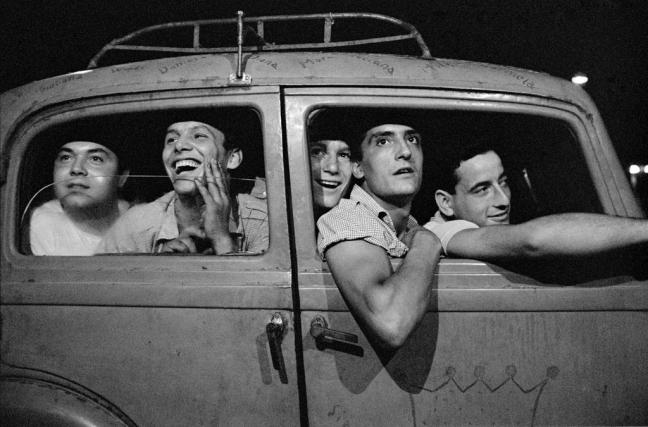

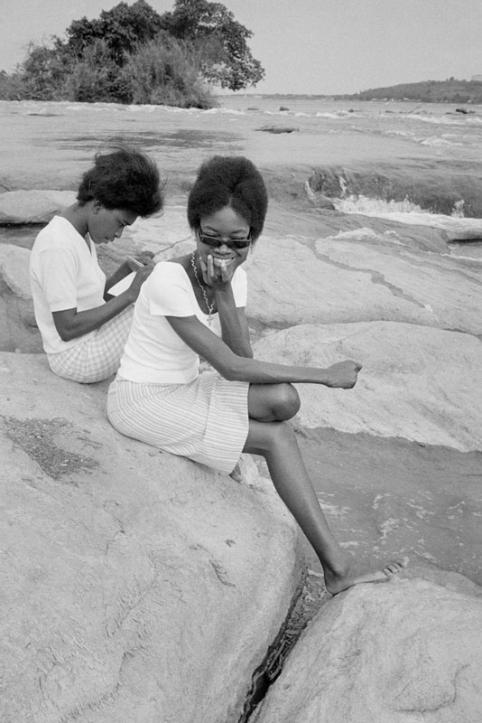

Léon Herschtritt [ b. 1936] was the youngest photographer ever to be awarded the prix Niépce in 1960 thanks to the work he did during his military service in Algeria. As a true humanist, he was quick to diversify his subjects, developing a particular sensibility for street scenes, young people in the sixties and their progressive emancipation, social movements, the gypsy populations…

Using the photographer’s personal archive and at times developing photographs from negatives that have not yet been used, this exhibition is based around eighty photographs that provide the viewer with an overview of Léon Herschtritt’s work in the sixties. In some way, his work bears witness to the end of an era.

This exhibition is made possible by the support of :

Canson, the Ministry of Culture / DRAC Bourgogne Franche-Comté and the Friends of the Nicéphore Niépce museum.

Léon Herschtritt’s work is a trial for the critic. The series emerge without having to be decoded. They are obvious. A prostitute shimmies, a soldier puffs out his chest, Parisian couples smooch on benches. Today, photographers are lauded for originality. Edginess is the rule and this is not a bad thing as conformism in photography lacks nuance.

However, we must not forget one of the medium’s essential qualities, to show things again and again and to comfort the memory. In this show, we retrace our steps. We take pleasure in going down well-worn paths. Today, who dares to paint the portrait of a country or a profession, who dares to feature lightness, joy, sadness and despair? Mood photography, is that in fact the simple definition of the work of Léon Herschtritt? Things aren’t that simple. It is a trial for the critic! As, given the agitation of our own constantly shifting present, we are not in a position to judge the era.

We lay claim to freedom of perception and nevertheless, we can’t help characterising this photography as melancholic. However, if we could, just for a moment, set aside that which is anecdotal and out of date, we would be forced to admit that the times were in upheaval. Behind the futile appearances, behind the equivocation, we can detect the premise of a dark future, our present. In the sixties, a time considered to have been “glorious”, nations were emerging, young people were preparing for rebellion, strikes were widespread and the world was splitting into two camps. In what seems to be an endless parade of shallow, carefree moments of grace, the photographer captures a real sense of movement, of both things and people. Today, we are aware of what nations were going through, from the fall of colonial empires to the culture crisis.

The not-so-humble photographer bears witness to the fragility of society and the futility of photography. It would be incorrect to take Léon Herschtritt for a photographer with a critical eye. Nevertheless, when he focuses on a subject, nothing is direct. His vision moves over that which is, to all intents and purposes, relatively incidental. Photography is not to be found in the answers it provides, and offers even less in terms of solutions, but it does question its participants, the actors or extras in this theatre.

Photography has never been as “devious” as to take us down a series of wrong paths and we would be mistaken to understand this way of diverting the issue as a “humanist” artifice. Léon Herschtritt gets away from the tragic, from excess and eye-catching contrasts so as to impose his lucid, clever, non-acrimonious photography. He finds the right level of expression of his work in a slightly nostalgic if somewhat sharp approach, structured around the way things and men work. The photographer’s main aim is to contain each image within a narrative that owes nothing to the great photographic works he knows and appreciates. He exercises the profession of photographer-reporter without shame, confident in the rough quality of the tool. The resources of the machine itself are enough for him to express that which lies beneath.

So it goes, the work of Léon Herschtritt, it lives without fits and starts, almost underground. In describing it one often is often misled. One could be led to think it was declining. Then, it is exhumed. It arouses more than curiosity. And, it is quite possible that one day it will awaken the uneasiness that brought it into being.

François Cheval