The work of Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand (b. 1945) formed a foundation for an entire generation of French photographers. Since 1980, the artist has incessantly revisited old techniques and original photography practices, taking a purely conceptual approachs. His images oscillate between scientific rigour and poetry.

Two complementary exhibitions, the result of a generous donation by the artist to the Strasbourg Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art and the musée Nicéphore Niépce, one in Chalon-sur-Saône and the other in Strasbourg, will provide a retrospective of three decades of experimental photographic creation.

At the beginning of the 1980s, auteur photography wanders halfway between the blunt observation of reality and its rejection. Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand’s approach then leads him to forge a unique and solitary path that eluded all affiliations. He’s convinced that the essence of photography lay in its act of birth, a gap between the intention and the print. He thereby resorts to historic quotation and obliges us to rethink the photographic act in its entirety, from the taking of the photo to the purpose of the image.

Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand has decided to redefine the founding principles of the mechanical image, drawing on the scientific history of photography. He has applied himself to discovering and experimenting with old techniques, from the daguerreotype to the chronophotograph: “This laborious handiwork should be seen as a nostalgic quest for the early years of photography, when all was yet to be discovered, with a box, a piece of glass, chemistry and chance.”

He thus enters the photographic act, drawing on the precepts of science. Photography can be compared to those 19th-century educational games, those cultivated and recreational ways of acquiring scientific knowledge. The method involves constant recourse to decoys. Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand plays with light, which he transforms into matter and matter into light. The photographer-physicist’s reasoning is based on the paradoxes of substance, space, time and movement, the physical, interchangeable data essential to the constitution of the photographic act. Optics and chemistry are the object of the experimental act. Each series is there to test empirically the pioneers’ intuitions.

He wants to go backwards, but only in order to free himself from all the discourses that weighed down and still weigh down the mechanical image. The attempt to come to terms with the first gestures and the first manipulations revealed his ambition: ridding photography of the noxious air of the realist utopia.

In parallel, another side of the “Colles et chimères” exhibition by Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand is on show at the Musée d’Art moderne et contemporain in Strasbourg from June 28th to October 19th 2014.

A book has been published to coincide with the two exhibitions by the éditions des Musées de la Ville de Strasbourg

Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand – Colles et Chimères

Nb of pages: 200 pages

Nb of d’illustrations: approx. 300

Biography /

The man is reticent about the events that have marked life, which are clearly not important to him. What counts are his thirty years spent grappling with technology, and the resulting images. The latter provide clues about this person and his obsessions, about a history whose chronology is of little importance. Nevertheless, when he is asked about the subject, here are a few of the times that he remembers.

Patrick Maître-Bailly-Grand was born on 1 February 1945 in Paris. His name – not a pseudonym as many have supposed – comes from his Franche-Comté origins. A large family house in the Haut-Jura formed the backdrop to his childhood. This formative place would provide the germ for the principal facets of his life. ‘My memories of childhood are those of a boy who was made to grow up far too quickly by his parents all too aware of their disillusionment with life.’

[1]

At an early age, in order to ward off the malaise of the people around him, he explored his creative potential. He painted on salvaged materials, and repaired and made things at every opportunity. This home also gave him a taste for beautiful and rare objects.

During the years of his youth, a strong yearning for science and technology led him to prepare the entrance exam to study engineering at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts et Métiers. He failed, but nevertheless conserved a precious memory of the preparatory classes where he discovered, among other things, technical drawing and machine tools. He subsequently took a course at the Faculté des Sciences de Paris and in 1969 earned a degree in fundamental physics. His student years were marked by the events of May 1968, during which he was politically active.

In the early 1970s, health problems forced him to change course. He chose painting, which he devoted himself to for a decade, developing a cold, analytical hyperrealist style. He used slow-drying lacquer and acrylic paints to create images with flat tints, devoid of perspective, which he says were influenced by Far Eastern art. ‘Traditional Japanese or Chinese art, with its calm, direct, contemplative imagery, fascinates me. I love those voids that give you room to breathe and where there are none of those oblique lines frogmarching you towards some divine destination or other.’

[2]

But in his painting, Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand soon came up against a form of exhaustion. The medium did not satisfy his fondness for seeking technological solutions. He found no ‘engineering escape’.

[3]

In 1979, he began gradually shifting towards photography. He grasped the possibilities of this tool as a visual artist at the same time as Madeleine Millot-Durrenberger, with whom he lived at the time, was discovering photography as a collector. They shared a passion for the work of Joseph Sudek.

But the only ‘master’ that Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand mentions is Etienne-Jules Marey, the father of chronophotography. This process making it possible to capture the movement of a subject laid the foundations of film technology. Although this pioneer’s ingenuity was one of the reasons for this admiration, it was above all ‘the great beauty and enigmatic character of the images’

[4]

that interested Patrick Maître-Bailly-Grand.

‘The discovery of photography gave me the feeling of entering a corridor containing a hundred doors to open, and I’m still there.’

[5]

This sentence aptly sums up the myriad character of the body of work that Patrick Maître-Bailly-Grand has been putting together since the 1980s. In his research he uses film techniques alone, exploring the metaphorical space where the photographic act draws as much on the medium’s history and its characteristics as the photographer’s imagination.

His first photographic subjects were architectural fragments and their shadows, urban landscapes shrouded in mist and approached frontally, in such a way as to make them almost abstract. Human figures are absent from them (Les classiques

, 1980–85). This outdoor work from life continued with prolonged interpretative work in the studio. The prints took the form of small black-and-white prints, some of which were touched up with lead pencil, recalling his training in technical drawing (Les noirs au plomb

, 1980). On others he experimented with very subtle split toning (Les brumes

, 1987; Les Statues de la Liberté

, 1984). He then devoted several years researching the daguerreotype, quickly coming to be regarded as one of the most important contemporary daguerreotypists (1983–87).

Throughout his career, his love of technology has been reflected in his use of ingenious systems harnessed to his reflection on the medium. He has said that he does not know how to photograph simply. Periphotographs (Formol’s band

, 1986; Recto-verso

, 2008; Trophées

, 2008, etc.), strobophotographs (Poussières d’eau

, 1994; Eaux d’artifice

, 2005), rayograms (La lune à boire

, 1991–94; Arts et Métiers

, 1999; Pâtés d’alouettes

, 2003, etc.), solarisations (Digiphales

, 1990; Romanes

, 1993, etc.), chemical toning (Les croix

, 1996; Mélancolies

, 2004, etc.), direct monotypes (Gémelles

, 1997, etc.) are as much means to appropriate photography itself as an attempt to thwart its apparent objectivity. But these complex tools also serve a fertile imagination fed with memories, emotions and sensations.

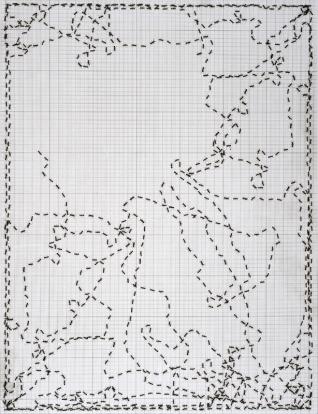

Quickly abandoning representation of the outside world, Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand gradually devoted himself to the observation of his immediate world. However, the subjects were extremely varied. The new themes tackled included living things, which appeared in his work via the movements of insects in enclosed spaces or on the artist’s table (Les araignées

, 1991; Les mouches millimétrées

, 1995; Vacances avec mes copines

, 2003, etc.). There followed imprints in jelly, reflections in glass, and the body’s shadow, all of which introduced a form of self-portrait (Les anneaux d’eau

, 1997; La main

, 1998; Endroit en verre

, 2003, etc.). The passing of time and movement were captured in a challenge to photography’s ostensible propensity for fixing the instant (Chronos

, 2001). Finally, the artist questioned and reinterpreted some archetypal images from the history of photography (Véroniques

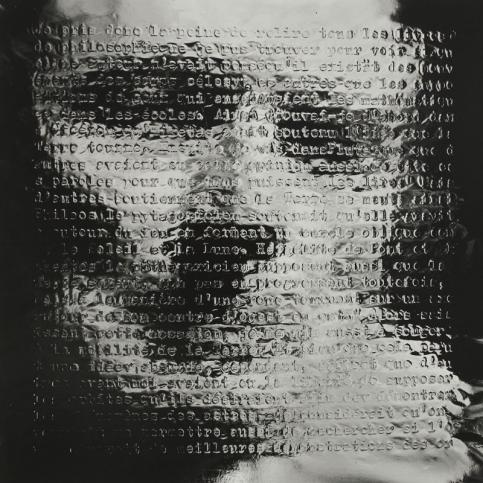

, 1991–94; Maximiliennes

, 1999, etc.).

Objects and their reappropriation also occupied a growing place in his work. As an aesthete and bargain-hunter, he created a collection that is today organised like a curiosity cabinet in the Strasbourg apartment that he occupies with his partner Laurence Demaison, also a photographer. Many of them have provided the starting point for photographic series referring to the theme of the vanities (Petites vanités

, 1998; Le péripatéticien

, 2006; Gueules cassées

, 2009; Les verroteries

, 2009, etc.).

The ‘orphaned’ photographs, picked up at flea markets, are also collectible objects that provide inspiration. ‘An interest in anonymous photography (or “pursuing chance”) is a cruel game of the last chance saloon for this multitude of small pictures of people, exiled in serried ranks in shoeboxes, a hair’s breadth from annihilation. . . . And then suddenly, amid this torrent of the ordinary: the NUGGET. A tiny little thing, more than or less than the ‘others’, which suddenly propels a small photo into the world of poetry and music.’

[6]

He donated this body of work to the Musée Nicéphore Niépce in 2012.

With the same aim of preserving the coherence of his work, which continues to grow thanks to his photographic experimentation, examples of Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand’s emblematic works have today joined the collections of two major public institutions, the Musée d’art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg and the Musée Nicéphore Niépce in Chalon-sur-Saône.

Anne-Céline Besson

Conservation assistant, Musée Nicéphore Niépce

[1] Patrick Maître-Bailly-Grand, Little Cosmogonies , 2007, p. 12.

[2] Patrick Bailly-Maitre-Grand, Little Cosmogonies , 2007, p. 13.

[3] Patrick Bailly-Maitre-Grand, interview, March 2014.

[4] Patrick Bailly-Maitre-Grand, interview, March 2014.

[5] Patrick Bailly-Maitre-Grand, interview, March 2014.

[6] Patrick Bailly-Maitre-Grand, Chasseur de hasard , p. ???, 1995