How to approach mass murder without falling into “compassionate” or strictly documentary forms? The Armenian genocide, unlike the Shoah, was revealed from the start through photography. Denounced in 1915 as a “crime against humanity and civilisation”, the facts were well known and covered by the international press.

A century later, Kathryn Cook takes on the Armenian question, approaching it through poetry and allusions. She handles the metaphor effectively, purposely getting lost between the past and the present in an in-distinction that blends history and the intimate.

In 1915 on April 24th, on signing a deportation act against the Armenian community, the Ottoman government organised the first genocide of the 20th century. The Armenians were then forced to walk across what we now know as Turkey with no food or water, on a difficult road, through deserted land, snow-covered peaks and arid plains. In order to escape certain death, many converted to Islam going as far as to hide their origins from their own children.

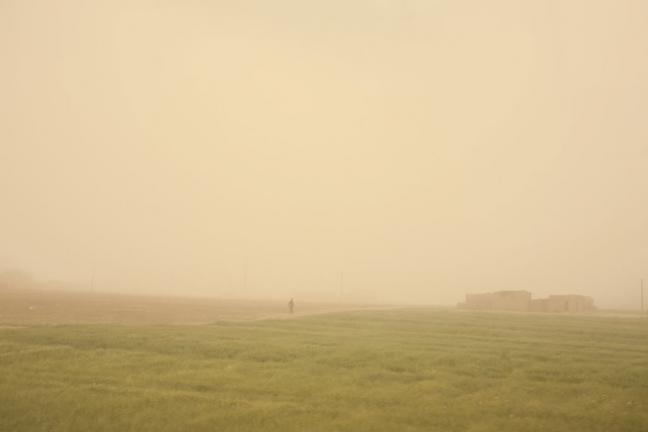

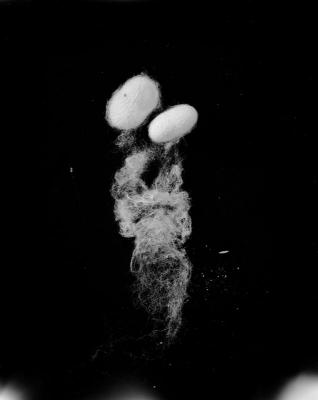

The American photographer Kathryn Cook (b. 1979) has been documenting the landscapes that provided the backdrop for these forced marches for a long time. She travelled to meet with the descendants of these deported populations, looking for their slowly revealed history. In the village of Ağacli in Anatolia (literally “the place of the trees”), where the Armenian community have been breeding silkworms for centuries, the silk-making tradition is being brought back to life by the Kurdish population. Only the ancestral mulberry trees bear witness to the Armenian presence. Kathryn Cook has taken it upon herself to collect the traces of a tragic past. By examining the consequences of the events that occurred in 1915, she is attempting to create an impossible representation of an invisible suffering, of old, unexpressed pain that needs to be exhumed, talked about and shared in order to build a collective future.

More than a century after the fact, the representation of the Armenian genocide, a tragic cornerstone in the history of mass murder, continues to call into question the very foundations of photography. What can be said of the incident ? That it took place, certainly. That, at times, it might feel somewhat’ overexposed’. It’s even become a historical axiom. If, for most part, the precise characteristics and causes of the genocide remain obscure, this is of little importance because the slaughter itself is incontestable. In defiance of reason, however, there is little interest in the contemporary repercussions of the massacre. Paradoxically; this may be an unexpected consequence of the abundance of proof.

We are not lacking documentation. We can count at least twenty public or private collections around the world that contain eternally unbearable images of events. All of which confirm, for those who need it, the reality of the 20th

century’s first genocide: more than one-and-a-half million Armenians killed.

The photography here, contrary to that of the Shoah or the Cambodian genocide, provided methodical documentation of the ethnic cleansing policy carried out by Turkish leaders: the destruction and pillaging of villages, the forced conversions to Islam, the massive deportations to the Syrian desert, etc. The massacres were on a scale never before seen and ushered in the mass violence of the 20th

century. As early as 1915, the acts were designated as’ crimes against humanity and civilization’ and were widely reported by the international press. Photography captured and catalogued indisputable proof of the ramifications of this union between age-old barbarity and modern logistics.

The photography of Kathryn Cook doesn’t need to provide testimony. Who knows why this American photographer, with her roots in the news media, wanted to grapple with the work of bereavement! By examining the consequences of the events of 1915, she attempts the impossible task of representing invisible suffering. She tries to develop a form for grief, to give shape to bygone, unexpressed pain. In the style of a road movie – or is it a type pf rite of passage? – the photographer is freed from the temptation of objectivity as she explores the sites of the Armenian people’s dramatic peregrination. More apprentice than investigator, dhe manifests a sense of impotence when it comes to providing an ‘objective’ account of the traces of the genocide. This is where documentary photography, and its mystical capacity to create a buzz, is called into doubt and reveals itself to be inadequate in the face of silence, amnesia, and, to say it all, the abyss. In search for the original manner of treating the Great Crime, Memory of trees affirms that rationality must be nourished by poetry.

François Cheval,

Extract of the book

Memory of trees

,

Editions Bec en l’air, 2013

Exhibition co-produced with Marseille-Provence 2013 and the MuCEM, Marseille

Kathryn Cook is a member of Agence VU’