Northern Ireland :

Gilles Caron + Stephen Dock

02.12 ... 05.22.2022

Opens Friday 11 February at 7 p.m.

Fifty years after the events of Bloody Sunday, this exhibition blends the historic and the contemporary to broach the Northern Irish question in all its complexity.

The Northern Irish conflict, commonly referred to as “The Troubles”, began in 1968. It tore a corner of Ireland apart, between republican nationalists (Catholic for the most part) and loyalist unionists (Protestant for the most part). It all began with a civil rights movement against the institutional segregation that mainly affected the Catholic minority. The rise of paramilitary organisations on both sides led to the situation escalating rapidly. The Irish Republican Army led a campaign of terrorist attacks mainly between 1969 and 1972. Northern Ireland descended into civil war.

This was a War of Independence for the nationalists and a fight for survival for the Unionists. From the very beginning, Gilles Caron was there to record the many facets of this extremely complex conflict.

Gilles Caron

Northern Ireland - 1969

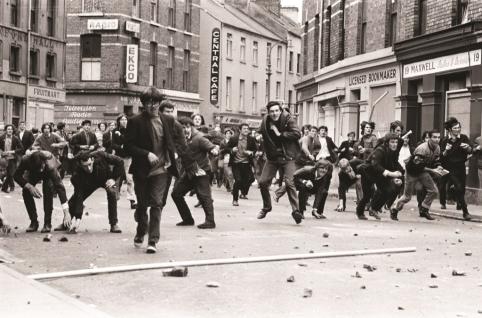

On August 12 1969, the Derry chapter of the Apprentice Boys, Unionist Protestants and members of the Orange order, held their annual parade close to a working-class Catholic neighbourhood, despite protests from the locals. This led to the Battle of the Bogside, thought by many to be the start of “The Troubles” in Northern Ireland. The British Army rolled in with tanks and tear gas as nationalists fought back with stones and Molotov cocktails. Two days later, while other uprisings were brewing elsewhere in the province, the British Army attempted to take back control. These events marked the beginning of a war that was to last thirty years.

Gilles Caron was in Derry on August 12, covering the Orange march for the Gamma photography agency. He had a feeling the violence was escalating and once he got there, he very quickly understood what was at stake.

It’s quite simple.

I was in

I

reland before anyone else.

The evening before the figh

ti

ng broke out,

I had arrived to cover a march.

Everything was calm, quaint even. The marchers

walked

by

peacefully

in

their

hats

with flowers in their lapels. A fight broke out around four o’ clock in the afternoon.

It started slowly, a few rocks were thrown, and t

hen it got out of hand as the protesters set fire to entire neighbourhoods. It went on like that for three days. We thought it would end as soon as it started.

In Paris

,

they thought

there was no point in

send

ing

someone. The demonstrators took the arrival of the British Army to be

a victory for the Catholics.

I thought it was all over and I was goi

ng to leave when things started up again in

Belfast.

I took a taxi from Derry to Belfast.

I worked all day and all night

then

got on a plane to London a

nd

gave my photos to a passenger who was

flying on

to Paris. That meant that Gamma had the originals the following day

before the slow coaches in the English papers

. The guys from Paris Match arrived on the Saturday

when I was leaving

.

”

[1]

Gilles Caron captured the tension as it built, from the first photos of the marching bands to the first rocks thrown. Very quickly, the police seemed to be overwhelmed and the city became a battleground. Gilles Caron watched as the shift occurred, this was not his first experience of armed conflict as he had covered the Six-Day War, the Vietnam War and Biafra. Through his lens, we see a country at war.

Gilles Caron’s work in Northern Ireland was published by many news magazines around the world and contributed to the conflict getting coverage very early on. In an issue dated August 30 1969, Paris Match

presented its readers with a full portfolio of five double pages of just photographs.

Recently, a book by Pauline Vermare

[2]

entitled Insurrections

provided a complete review of the reportage archives and a written piece of reference. She points out: “These pictures evoke the gaiety of May 1968 and the gravity of the armed conflicts that Caron covered. This tension is what makes this reportage so powerful. By following history in the making, hour by hour, day and night, from Derry to Belfast, Caron is the only person who was there to bear witness to the fundamental turn things were taking for the people of Ireland: state of peace, state of siege, state of war.”

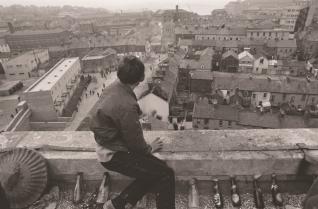

In addition to being “first” on the scene, the modernity of Gilles Caron’s photographic approach makes it exceptional. His work is in constant movement, shot/ reverse shot, from the top of a building, at the corner of a street; in one camp, then in the other. He gets close to the scene, he goes, he comes back, and stops at a strategic spot. At times it feels like he is ahead of what’s happening.

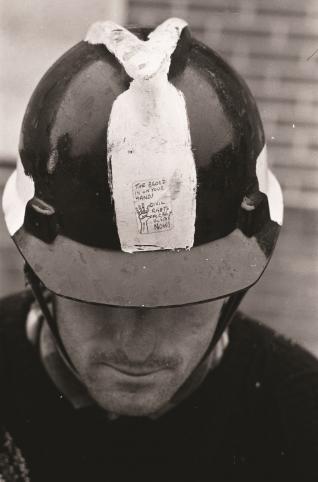

In the middle of the chaos, he pays attention to individuals, main characters or anonymous figures. He takes the portrait of Bernadette Devlin, a leading figure in the civil rights movement in Derry, and that of a young boy with a gas mask that ended up on the cover of Paris Match, icons both. That picture even became the subject of one of the world-famous murals in the Bogside. Other shots, away from the reportage, do not seem destined for a newspaper. Street scenes or portraits away from the conflict, help to build the narrative, to express the tragedy. Through these pictures, Gilles Caron invites the viewer to question themselves and opens the way to new forms of photojournalism.

In his book Gilles Caron, Le conflit intérieur

[3]

, Michel Poivert writes: “Caron’s ambition was to talk about the news in a different way, to integrate his own feelings about humanity to the visual stenography of photojournalism. This attempt to find a new frequency between the outside and the inner life now seems like a foreshadowing of the following decade’s auteur

photography.”

In four days, sixty-two black and white rolls of film and almost three hundred colour shots, Gilles Caron crafted one of his greatest stories; a unique testimony of this turning point in history. Visitors to this exhibition will get to discover his work, beyond the iconic pictures published in the press at the time. It includes seventy photographs, vintage and modern prints, as well as enlarged reproductions of contact sheets that highlight the photographer’s process.

The museum would like to thank the Fondation Caron, the Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine and

Fannie Escoulen for their support in putting this exhibition together

.

[1] See Jean-Pierre Ezan, interview with Gilles Caron, Zoom n°2 March-April 1970

[2] See Gilles Caron, Insurrections, Irlande du Nord 1969 - Text by Pauline Vermare - Editions Photosynthèses, 2019.

[3] See Gilles Caron, Le conflit intérieur, Editions Photosynthèses, 2013

Stephen Dock

Our day will come

Our day will come. The popular Irish Republican slogan evokes the hope for freedom and the wish to vanquish the other side. Words that cannot be said without thinking of the day of our own death.

Stephen Dock started as a photojournalist at a very young age. In 2008, when he was barely twenty years old, his only ambition was to seize the moment. Ever eager to inform, he followed stories to the world’s most dangerous hotspots, Syria, Palestine, Mali, Iraq... War zones became his chosen field, conflict an everyday occurrence. Very soon however Stephen Dock started to ask himself questions. Was he attracted to battlefields because of his own pain, his own inner conflict? His soundless stories expressed his personal battle, the inability to find peace.

Dock decided to take a different path, he started working in a blend of colour and black & white, enlarging certain details, reframing stories. The approach was more personal, the writing more poetic. Photography allowed him to talk about the world and talk about himself. Inside and outside were no longer disconnected. As Gilles Peress puts it “He always photographs from the inside to the outside and not the other way round” freeing up his side step.

The “New IRA” formed in Northern Ireland in 2012. Stephen Dock decided to go to Belfast for the centenary of the Ulster Unionist pact. The tension was palpable, but nothing happened. The time for armed conflict was over. The Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, putting an end to thirty years of civil war. But the souls of the people were not at rest, and ancient foes lived together in a fragile peace.

People from both sides of the conflict are, to this day, haunted by an inner violence that is cultural, social and political. It marks the faces of the survivors and those of the younger generations. It wields a power much stronger than physical violence, shaping behaviour, becoming an invariable that is handed down from one generation to the next. If the hate between communities sculpted Northern Irish identity, it has also left a long-lasting mark on the province. Life goes on around the “peace lines”, the “peace walls” that began to appear after August 1969. Dotted around the cities of the province, they separate the inhabitants of the same neighbourhood, at times even the same street. The stigmata of war are everywhere. Huge murals pay tribute to the “heroes” of the conflict, painted messages warning strangers that they are entering republican or unionist territory. The walls speak. Graffiti shows allegiance to dissident groups, voicing support for those in prison, or protesting the occupation: “Brits out!”

Marching season is an annual event, with parades, marches and bonfires of wood palettes that can reach thirty metres high, on which the Irish flag is burned, or the Union Jack. Each event is deeply political and underscores the partition. The division is entrenched affecting daily life down to the tiniest detail.

The question for the photographer was how to render this latent conflict that has opposed two communities for hundreds of years? How was he to represent a society that is this divided? To find an answer, Stephen Dock travelled to Northern Ireland eleven times in six years. He tried to understand the impossibility of peace, something he felt himself. The resulting body of work is made of things and signs from everyday life: portraits, architectural details, street scenes… The photographer chose traces, at times infinitesimal, left by the conflict, and made them visible.

Biography:

Stephen Dock was born in 1988 in Mulhouse. He lives and works in Cambrai.

From very early on he worked in the field, travelling to Venezuela, to Nepal, to the West Bank, to Syria, to Iraq, to Northern Ireland, to the United Kingdom, to Mali, to the Central African Republic, to Lebanon, to Eritrea and to Indian Kashmir. He was represented by VU’ from 2012 to 2015 and was a finalist in the Leica Oskar Barnack award in 2018, finalist in the Prix Découverte Louis Roederer in 2020 special prize-and winner of the Prix LE BAL for young artists from the ADAGP in 2021. His work has been shown at the Leica Gallery during Paris Photo, the Tbilisi Photo Festival, the Visa pour l’image festival, the CNAP, the MAP Festival in Toulouse and at the Bayeux Festival. He has been published in French and international publications such as M le magazine du Monde, Le Figaro Magazine, Newsweek Japan, Paris Match, Internazionale, VSD

and Libération.

The museum would like to thank Canson and Fannie Escoulen for supporting this exhibition

.

The prints were developed and printed in the museum’s laboratory on Canson Infinity Arches 88.

Stephen Dock’s work was produced with support from the CNAP - Centre National des Arts Plastiques.