Alexis Cordess / anglais

The prints of series Itsembatsemba

and Juliette

for the exhibition were produced in the laboratory at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce on Canson Infinity Rag Platine 310 g. and the series La Bruja

on Canson Infinity Baryta Prestige 340g paper.

The museum would like to thank: Canson, La maison Veuve Ambal and La société des Amis du musée Nicéphore Niépce.

Publishing:

Alexis Cordesse,

Talashi

Atelier EXB,

Éditions Xavier Barral

Bilingual French-English,

16,5 x 23,5 cm

128 pages

55 photographs in color

35 euros

Isbn : 978-2-36511-318-2

In library,

Oct. 7th 2021.

Presences

Today’s networks and the flood of data have led to the trivialisation of press photography. Digital technology has turned each and every one of us into potential witnesses and producers of pictures. This instantaneously uploaded content creates the illusion of a hyper-visible world orchestrated by huge media networks that dictate a regime of urgency and immediacy. There are so many pictures out there that we zap more than we look. The sheer volume of content means each quickly glanced at/ quickly forgotten picture is given the same weight. When timeframes are so short and the present is all that matters, there is little room for analysis or long reportage work that requires time, thought and long-term involvement. Alexis Cordesse was born in 1971 and started working as assistant to Gianni Giansanti in 1990, before going to work as an intern at the Sygma photo agency. The following year, he took his first photographs in Iraq, at the end of the first Gulf War, a war “without pictures” that was to push news coverage into the age of suspicion. His influences came from photojournalism but he soon found himself straining against the confines of press photography. Formats and layouts dictated editorial decisions and magazines tended to consider photographers as mere illustrators. Print media was already suffering from the onslaught of television news since the early seventies, and in the early nineties, the recession hit hard. The arrival of the Internet only exacerbated the problem.

Cordesse changed his approach radically during a reporting assignment in Kabul in 1995. He took the shots he was expected to take, but, at the same time recorded sounds, changed viewpoints, and started to make films using his photographs. His approach has been evolving ever since. He revisits various genres (portraits, panoramic shots, landscapes), examining the responsibility of the photographic image and its imaginary potential. He reinvents lengths and distances, goes off-centre, imposes his own demands and choices, and puts words to his pictures. For him photography has become one tool he uses among so many others to bear witness to the complexity of the world. In the process, he has forged his own testimonial ethos. This exhibition proposes a retrospective of Alexis Cordesse’s work in the form of ten collections, some of which have never been shown in public.

Kabul, A Weary War

1995

In the war-torn Afghan capital, plagued by rival militias, Alexis Cordesse recorded sounds and took photographs, mixing action shots with more contemplative work. This marked the first time he stepped away from pure reportage to produce a series of short films.

Itsembatsemba

1996

L’Aveu

2004

Absences

2013

Over a period spanning eighteen years, Alexis Cordesse produced three series on the genocide of the Tutsi people in Rwanda. He was aware that photography was limited when it came to bearing witness to a tragedy so complex and so extreme that any attempt to record or represent it was impossible. Instead, he took the shortcomings of the medium into account and added archive material and numerous interviews to his photographic approach. In Itsembatsemba

, Alexis Cordesse photographed what happened after the genocide, bodies being exhumed, commemorations for the dead and survivors in psychiatric hospitals. The combination of his photographs with extracts from Radio-Télévision libre des Mille Collines (RTLM), the propaganda channel used by those perpetrating the genocide to spread hatred, adds another layer of meaning. The words and voices contaminate and complexify the visual representations of the horrors to remind us that any extermination, before becoming an act, is an idea, a word, born from a human mind.

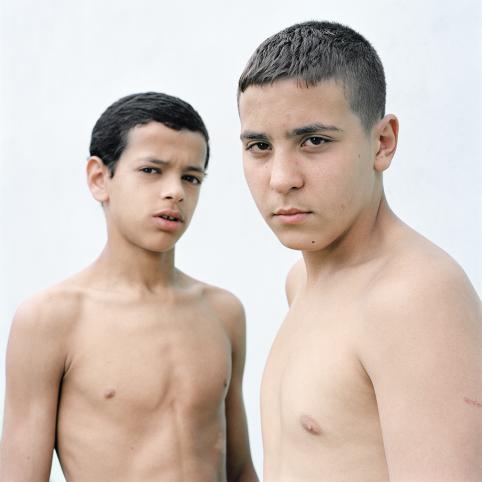

In L’Aveu

, Cordesse photographed the perpetrators of the genocide according to a strict protocol: dark backdrop, neutral lighting, frontal shot in colour. The portraits come with extracts from interviews he conducted with the subjects. For Cordesse, genocide is an inhuman crime, committed by humans. He considers the perpetrators of the genocide to be “in our likeness” to use Georges Bataille’s expression; his portraits attempt to reveal the ambivalence and complexity of these people without making any moral judgements. He avoids all dramatic effects, working at the same height as the subjects, varying his framing and continually asking himself questions, asking us questions: from what distance do we look at these men and women?

The final part of the trilogy is a series made nineteen years after the fact. Playing with the old colonial cliché that referred to Rwanda as “a paradise with a thousand hills”, the Rwandan landscapes in Absences

are devoid of any human presence, instead revealing a luxuriant view of nature that invites contemplation. No trace remains of the events, except for a complete list of the victims on a memorial wall, a commemoration scene shot from afar and the voice of three women, two survivors and one “just”. Faceless witnesses, who tell us what happened to them in this apparently tranquil place.

Borderlines

2009-2011

Borderlines

, sees Cordesse revisiting a photography classic – the panoramic shot – using contemporary digital techniques. He examines the question of borders in the Holy Land, a place that is saturated with media stereotypes where there is always something happening. His project is two-fold, to bear witness to the fragmentation of a territory where separation is the watchword, and to use photographs in composite form to create depictions that blur the lines between description and fiction.

Talashi

2018-2020

Talashi

is a “appropriated” piece that has never been shown in public before, made up of the personal photographs of Syrian exiles that Cordesse met in Europe and in Turkey, and who agreed to hand them over to him. The piece blends the intimately personal and the historical. The everyday images chosen by Cordesse are all familiar to us. Removed from the current affairs and news stories that surround them, they allow us to imagine and empathise with the lives of these ordinary people, that have been turned upside down by extraordinary events.

Olympus

2015-2016

A Greek friend once told him “You should climb Mount Olympus”. Cordesse was in Greece for a job on the political landscape in a region that the weather suddenly made inaccessible. Instead, he climbed up the legendary domain of the Gods, that he never even knew existed geographically until that very moment. Climbing the mount takes physical effort and awakens the senses. The physical, not mystical ascension, puts the climber into a particular mental state. He undertook the climb six times, and each time had the same feeling of connecting with the world.Cordesse later associated the exceptional images that came

out of this unexpected experience with snapshots of his everyday life. Olympus

is a meditative, pensive piece, a complex ensemble with no documentary logic that creates a secret echo. In addition to his work outside of press photography, Alexis Cordesse is also a portrait taker of note. The exhibition will present two iconic series that show his approach to the portrait, giving visitors an opportunity to discover work that has never been seen. In these three ensembles, the timeframes are long, the work happens year after year, and the repetition creates a form of trust and complicity with its subjects.

La Bruja

1999-2001

Cordesse retired to Cuba after ten years of working in conflict zones. When living in Havana, during a trip up the island’s east coast, he discovered the village of La Bruja. Located at the foot of the Sierra Maestra, it is a particularly remote place and it can take days to get there sometimes. He stayed with Lela, who lived in the only solid house in the village. To thank her, he took her portrait with a Polaroid. The first shot led to others. The village inhabitants came, one by one, dressed in their most beautiful clothing. Alexis Cordesse went back to the village regularly over three years and became the village’s official photographer.

La Piscine

2003

Summer 2003, the aquatic centre in Châtillon-Malakoff in the southern suburbs of Paris, became an