Jean-Christian Bourcart

An excuse to look, archives 1980-2000

06.16 ... 09.16.2018

extended to 09.23.2018

A friend of mine came by and told me to show my work to the reader’s page at Libé . Jean-Marie and Sophie who work there wanted to publish some of them. I would often go to see them in the basement on rue Cristiani... Jean-Marie published one of my photos – a cow with two extra legs on its back – to accompany letters from people who were ill. The editorial board put a stop to the reader’s letters page, on the pretext that they were shocked at the bad taste”.

The exhibition is curated by: Sylvain Besson / musée Nicéphore Niépce, Jean-Christian Bourcart and C.O. Jones. The exhibition comes to you with the support of DRAC Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. The musée Nicéphore Niépce thanks the Société des Amis du musée Nicéphore Niépce as well as Canson.

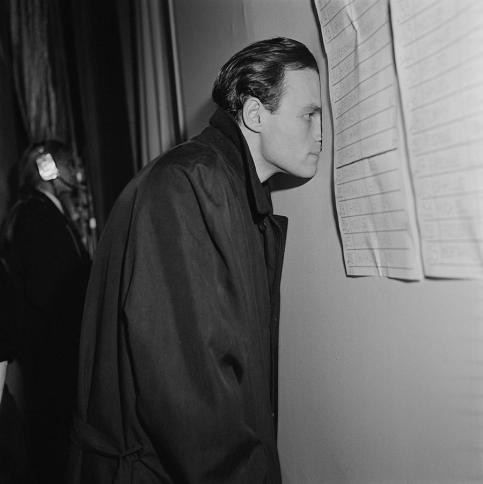

Jean-Christian Bourcart’s first steps at Libération

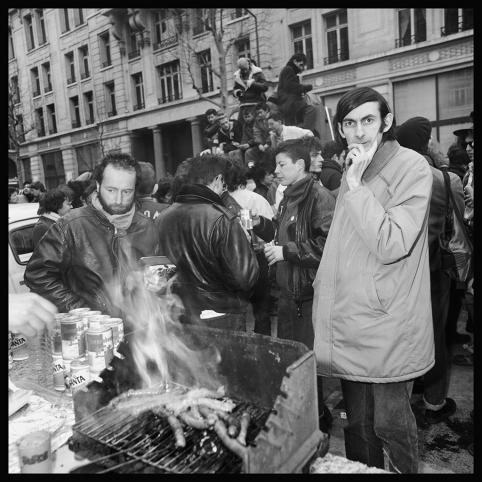

set the tone for his singular vision of photojournalism. In the 1980s, the newspaper was moving away from Jean-Paul Sartre’s original, founding message from 1973: “People, speak up and don’t stop”. The newspaper had suspended publication for the first time and reappeared on May 13 1981, a few days after the election of François Mitterrand as President of the Republic. The paper then entered a golden period. The country was going through an economic recession and the “social democrat daily with libertarian tendencies” adhered to and chronicled the cultural transformations of the French left.

It was the voice of the urban middle classes and reached its highest circulation figures in 1988, at 200 000 issues.

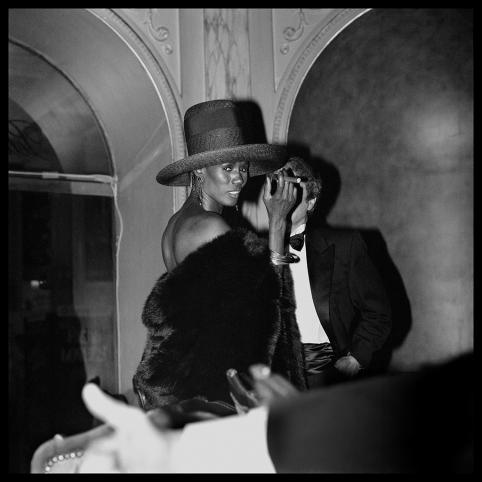

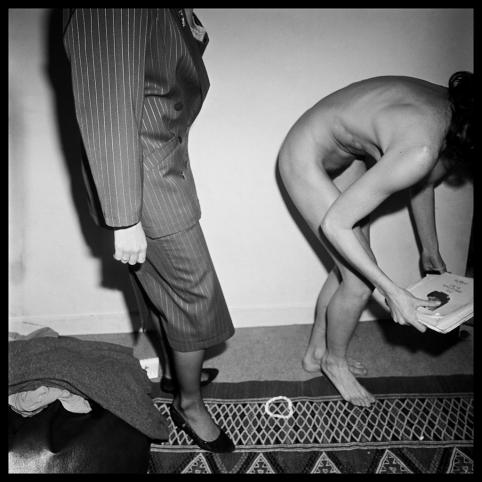

Culture was the main topic of the newspaper which made it a “must-read” for its demanding readership. The tone was set by an eye-catching and often provocative front page, and photography provided an original form for an editorial line that was unique in France in the 80s and 90s. Photography at Libération was far from being a style exercise. Few of the photographers were aware of the layout’s references, “VU” was now just a model for Christian Caujolle, the man behind the paper’s photographic policy. Photographers took their influences from elsewhere. Rock and roll, and in particular, punk rock was prevalent, nightclubs popped up constantly, sex was everywhere, underground literature and drugs were a huge part of the scene. This backdrop provided inspiration for the work, often encouraged and supported by the paper’s editors. The relationship between the pictures and the writing was set down by journalists who saw no difference between their personal lives and their journalism. Writers like Serge Daney, Michel Cressole, Hélène Hazéra, Alain Pacadis, much to Serge July’s chagrin, produced a daily that is more like a magazine!

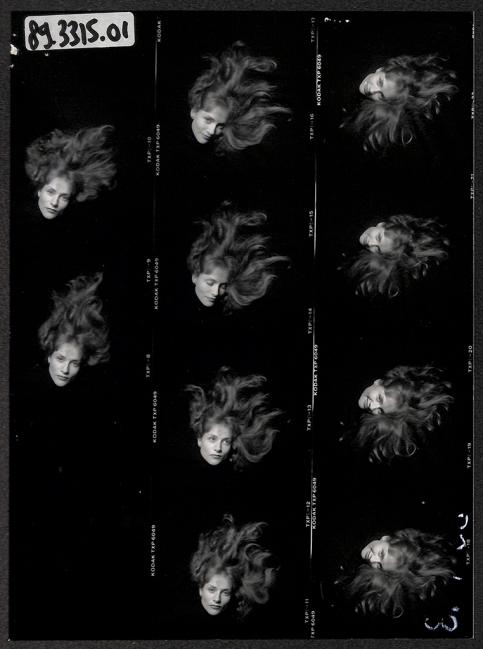

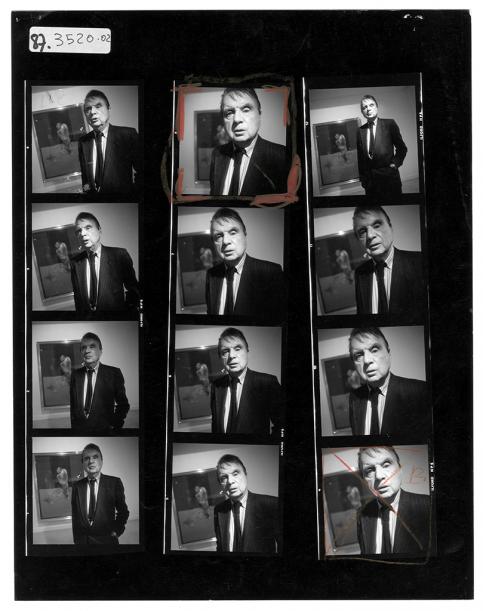

The photographer at Libération was a master of time. He or she was the image-maker, as defended by Christian Caujolle, head of the photographic department from 1981 to 1985, as opposed to being the simple illustrator the editorial departments wanted them to be. The image spoke to the text. No longer reduced to a mere legend, the commentary and the image were one as they were complementary. In this way, photography at Libération was documentary, with one main difference, the approach was one of closeness and empathy.

The ambition was to give the double pages life, to find a rhythm between the various types of signs. The eye was not supposed to rest if the image questioned it. It came with an emotional charge, based on the photographer’s own commitment, as an auteur who was naturally suspicious of the pseudo-neutrality of the job at hand. A reportage was never just a suite of icons and information. The concept was not a million miles away from Rodtchenko’s proposition, the single series could bear witness to a situation: “It must be made clear that documentary photography never provides an absolute portrait!” Images followed on from one another in a clarifying narrative. Temporal, circular sequences extolled material that was thick, foggy, contrasted. Coherence was possible only in the affirmation of an “ethic” where truth was not a subject in itself. The commitment of the photographer, his or her willingness not to dress up the real, to truly feel it and present it in its rawest form, was the crux of the issue. One picture, as part of a whole, was just one element, often a weak one, that only found its true place as part of a series. As in life, photography had its ups and downs. In this redefinition of reportage, Libération was unique in that it never judged what was being shown. “Modern” reportage called for going beyond the merely informative. Getting closer to people and situations was the photographer’s only objective who often used his or her personal experience as the very subject of a documentary project aimed at all of society. Examining the world was a question of aesthetics and semiotics. The photographic document, published and reproduced, was a project that depended on luck to an extent, but that transcended it to follow the publication’s plan.

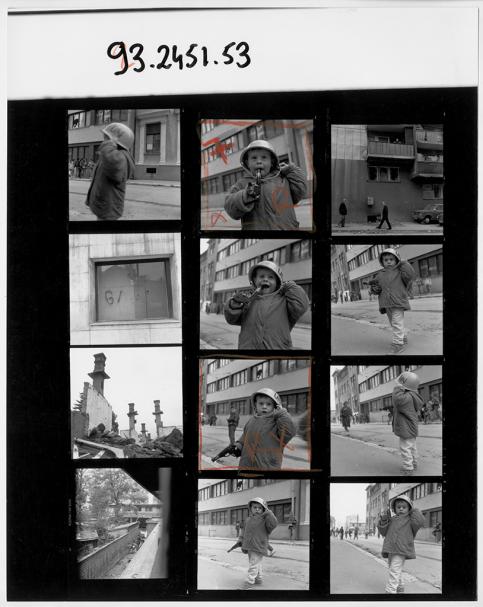

The paper’s photographic approach was unique because of the way photographs were commissioned. In 1994, Christian Caujolle, made reportage the emblem of an “unease felt by photographers about the press, that revealed the way “auteurs” were obliged to question the relation to the real, the “realism” of the images, their use and the aesthetics”. Irreverence was the common signature but the model remained literary. The paper brought new things to the table every day. Nothing was sugar-coated. The general framework took a back seat to the salient traits. Images presented situations and characters that were often anodyne, with no introduction or explanation. In a text published in 1973, in Cause commune , Georges Perec expressed the feelings of a generation that no longer recognised itself in the daily press: “Newspapers talk about everything, except the everyday things. Papers bore me, they don’t teach me anything; what they print is of no interest to me, doesn’t question me and neither does it answer the questions I have or I want to ask”. Photography was to be an attempt to banish the extraordinary in order to redefine the notion of an event, depicting the banal, the normal, the everyday, the little nothings that give existence a real meaning. Jean-Christian Bourcart’s work looked for “news” in moments that were considered to be unimportant. Portraits and situations came together to form a vast continent that was without any surprises but was extremely real. It constituted a form of photography that was both flat and hysterical. His work told stories that could conceivably happen to the reader. The narrative, we’ve already pointed out, was not there to exhaust the subject. The writing was fragmentary on purpose, even elliptical, but all of the subjects dealt with in Libération provided an anthropological inventory of France. The typical Libération photographer, in particular Bourcart, could not be referred to as an anthropologist, but the publications must be seen as attempts to go outside the box, a refusal traditional news. This way of working presupposed a commitment from the photographer, a way of going down roads less taken that was not the accepted practice in the big photography agencies of the period. For a time, Viva and Sipa managed to express this paradigm shift, the attempt to make the everyday more theatrical: “the art of documenting the inability of monopoly capitalism to create truly human living conditions…” [ Allan Sekula].

In fact, what Bourcart did was take portraits of the unique. From the mental patient to the weight lifter, from the politician to the night clubber, one “life story” followed another. The photographer was thus the centre of the newspaper’s paradox. At the end of the 1990s, the daily still had photographers that subscribed to the 1973, manifesto: “People, speak up and don’t stop”. The photography built a world, brick by brick, character by character, and appropriated a reality that was made from simple situations and words. Unlike the glorious elders [Magnum], its photography narratives were not aiming to be works of art. The world was an exchange between the person taking the photo and conscious, trusting characters. The task was complex. The traps were legion, as one had to make sure to adopt a non-causal point of view, to hide aesthetic criteria of class under a bushel, and above all, never to add to what others were saying, the pitfalls were too numerous. The “great narrative” remained tempting for the photographer who saw himself as another Capa or Caron! Some were able to resist the sirens. They managed to treat photographs as significant artefacts, and not as privileged objects. As such, they can be seen as anti-humanist!