The second part of the Think / Classify exhibition invites the public to continue discovering the museum's collections with a renewed display of works.

To celebrate its 50th anniversary, the Musée Nicéphore Niépce (1972) will lift the veil on what the public never sees: the storage rooms, the wealth of its collections. It is impossible to show everything, and even making a representative selection is difficult. An upcoming catalogue will retrace the history and the museum’s acquisition policy. Consequently, in order to give a feeling of the diversity and size of the collection and avoid doubling up with the permanent one, this approach is more poetic. The idea is to invite the public in to have fun with the spaces, inspired by Georges Perec.

Perec (1936-1982), known as the “mad taxonomist” was an adept of classification, lists and inventories. In an essay entitled Penser / classer

(Think/ Classify

), he ironically questions this anthropological obsession with trying to impose order on the world. Humans feel the need to sort through the world in order to understand it, to think it through. A place for everything and everything in its place. This overriding “obsession” is at the heart of museum life and activity. Regardless of its field of expertise, a museum acquires, sorts, classifies, preserves, transmits and shows.

This has been the mission of the Musée Nicéphore Niépce for fifty years, focussed on one subject, photography.

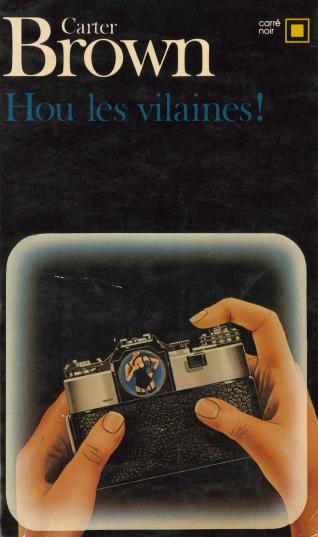

Images within images.

From the very beginning, photography carried a fixed idea, a utopia, at its heart, born out of the revolutions of the 19th century. The belief that through photography, we can show everything, and bring the entire world into a museum. The belief that we can make a universal and exact statement about things, and preserve a living image. The belief that we can win out over the passing of time, forgetting and destruction. Furthermore, the belief that we can better know and understand the world, by detailing, unpicking, examining it from every angle, from the infinitely huge to the infinitely tiny.

Photography kept its side of the bargain as is evident from the storage rooms of the musée Nicéphore Niépce. For two centuries, photography has, without a doubt, fulfilled all of our individual or collective taxonomic obsessions, whether they are scientific or documentary, amateur or artistic. The nature of the museum’s collections and the way they are organised can sometimes bring on a form of Perec-ian dizziness. Perec’s lists can also be applied to photography: “arrange, catalogue, classify, cut up, divide, enumerate, gather, grade, group, list, number, order, organise, sort”

. Then “subdivide, distribute, discriminate, characterise, mark, define, distinguish, oppose, etc”.

However, contrary to what they entail, none of these operations can be said to be objective. There is no such thing as neutrality and exhaustiveness. Everything comes with a certain perspective, decisions made in advance, off camera.

Thankfully, as Perec reminds us with humour and humility, our quest for omniscience is doomed to failure. By the time we finish them, our attempts to organise knowledge are often obsolete, and perhaps “barely as effective as the initial anarchy” …

Curator: Emilie Bernard, musée Nicéphore Niépce

The museum would like to thank Sylvia Richardson, Bernard Plossu, the Société des Amis du Musée Nicéphore Niépce and our partners, the Maison Veuve Ambal and Canson.

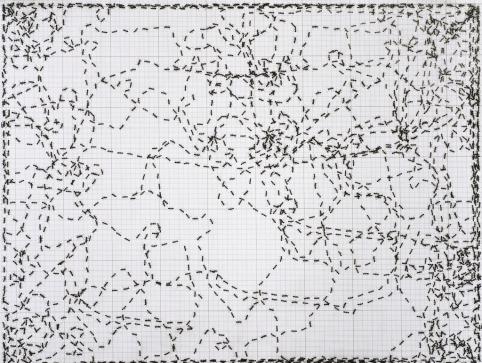

Entre sciences et poésie, le « photographe-physicien » Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand (1945) travaille sur la matière, l’espace, le temps, le mouvement, avec les principes originels de la photographie. Ici, il s’agit de mesurer et révéler le trajet d’une fourmi sur du papier millimétré. « La construction de ces images est complexe (enregistrement du parcours, sélection des différentes attitudes, collages, tirage via des papiers huilés, etc) mais cette jonglerie technique n’a guère d’importance pour moi. Avant tout, c’est un hommage à ces voyageuses qui, pendant nos siestes sous un arbre, dépassent largement les frontières de notre transat. » (Patrick Bailly-Maître Grand)

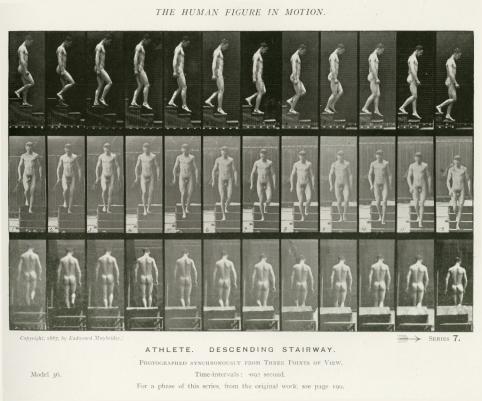

Le britannique Eadweard Muybridge (183O-19O4) inspiré par les travaux d’Étienne-Jules Marey(chronophotographie), invente en 1878 un dispositif photographique de décomposition des mouvements, composé d’une douzaine d’appareils à déclenchements successifs. Ces nouvelles représentations font l’objet de deux livres, Animal locomotion, et The human figure in motion. Muybridge, comme Marey, font figure de précurseurs du cinéma.

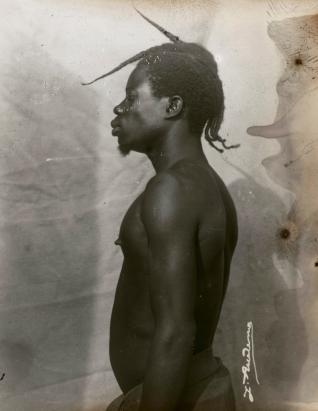

Membre de l’administration coloniale en Afrique équatoriale française, les photographies de Jean François Audema (1864-1921), représentant les populations et les activités coloniales, sont éditées et diffusées en cartes postales avec la mention « Collection J. Audema ». En 1897, alors qu’il est en poste à Luango (Congo), il photographie le passage de la mission Belge Behagle-Bonnet de Mézières et celui de la mission Marchand. Le musée Nicéphore Niépce conserve un ensemble de 71 plaques de verre de cet auteur et de cette période.

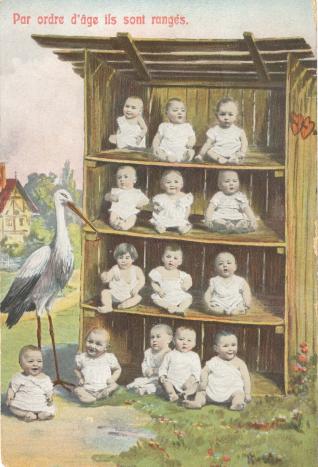

Par l’exercice du photomontage (découpage, collage) pratiqué dans ses archives personnelles, Christian Milovanoff (1948) associe des images, qu’il en soit l’auteur ou non, et les fait résonner entre elles. Cette mise en ordre du chaos visible crée du sens, des récits, entre documentaires et fictions