Papers, please !

This exhibition title in the form of an injunction aptly underlines the relationship between photography and law enforcement, which dates back to when it was first used in the court process in the middle of the 19th century. At some point in time, we have all had to present proof of our identity, an exercise

that if it does not define who we truly are, is the inescapable manifestation of our legal identity. Ever since it was invented, photography has ceaselessly complied with the requirements of identifying people and the desire to put them on file, a theme that is still topical today. Based on the musée Nicéphore Niépce’s collection, this exhibition aims to present an [inevitably incomplete] view of photography’s ambiguous relationship with this role that it has had to assume and the whole question of police records.

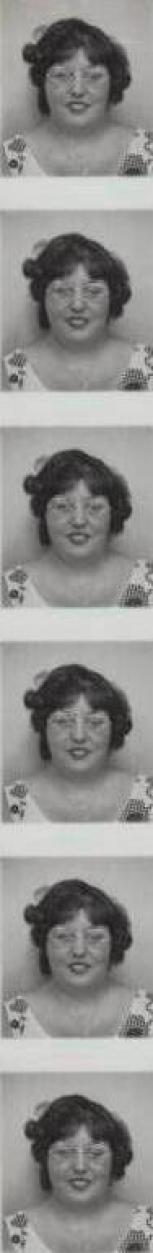

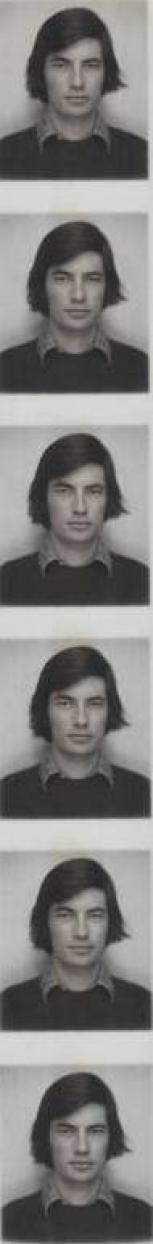

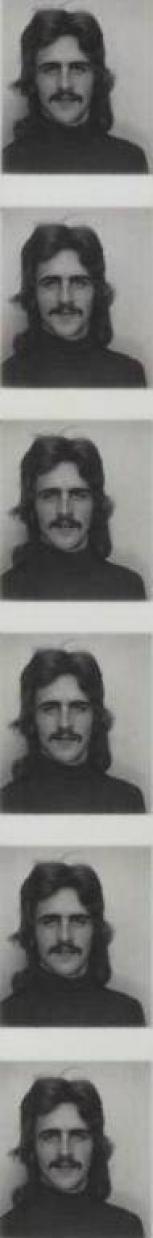

Photography provides a frame of reference, an interpretation of the meaning of identity, from having a passport photo taken to presenting your driving licence to the police, or from a census for national service to registering the identity of migrants. If the standards applied and the repetitive nature of the process lead to a form of depletion that is an integral part of the process, the images nonetheless reveal hidden meanings and sometimes exhibit more than what was expected and intended. In part a means of organising society and partly a system of surveillance that exposes the temptation to curb personal freedoms, the image-based registration and classification process unintentionally reveals – in its mistakes, blunders and omissions – a whole world outside the camera frame made up of discrepancies, absurdities, fantasy and imagination.

There’s no escaping it

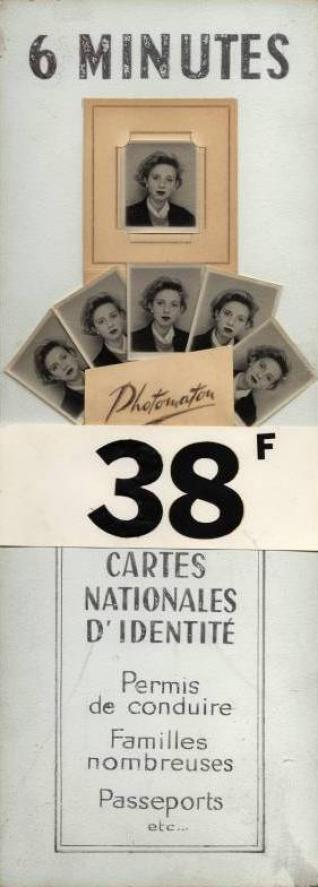

Whether it’s for a driving licence or passport, a travel card or a student card

or even in some countries your national health card, one day or another we all have

to go through the troublesome process of having our ID photo taken.

In line with the anthropometric principles established by Bertillon and, irrespective

of whether the photo is taken by a professional photographer or in a photo booth,

it must comply with a certain number of criteria and standards that determine whether

the image in question is acceptable or not for official use.

In France, it was during the Vichy regime that the obligation to record the identities of the entire population was instituted, thereby widening the scope of the identity controls that were until then reserved for minorities who were considered a danger to society. On the other hand, identity papers have been required to leave the French territory since 1913, an obligation that was implemented both with an eye to restricting circulation between France and foreign countries and to hinder the arrival of foreigners. So in fact, the original idea behind ID papers was all about controlling the borders, which is pertinent in our current times when the flow of migrants and the free circulation of people have become once more major political and social questions.

Photography at the service of a system

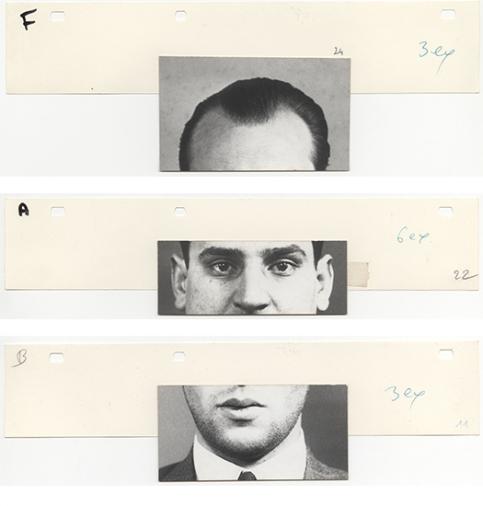

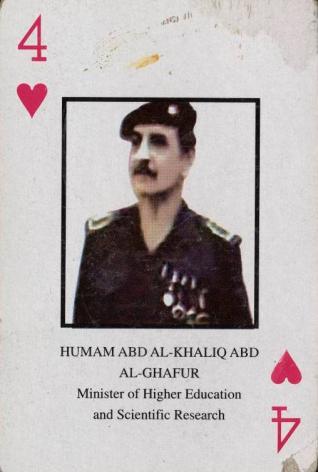

The French police photograph system, which produces what are more commonly known in English-speaking countries as mug shots, was created by Alphonse Bertillon [1853-1914] and such photos are still a central element of police records today. Bertillon is an emblematic figure in the history of the French police to whom is attributed the creation the first police forensic laboratory. In 1881 in Paris, in a general political context marked by the battle to reduce the number of repeat offenders, he devised a system using anthropometry for criminal identification purposes: a system of measurements and physical characteristics that placed the body at the centre of the identification process. In 1888, Alphonse Bertillon completed his system by standardising the mug shot, which henceforth had to be taken from the front and in profile. He codified every aspect of the process [the camera used, the subject’s pose and distance from the camera, as well as lighting etc ].

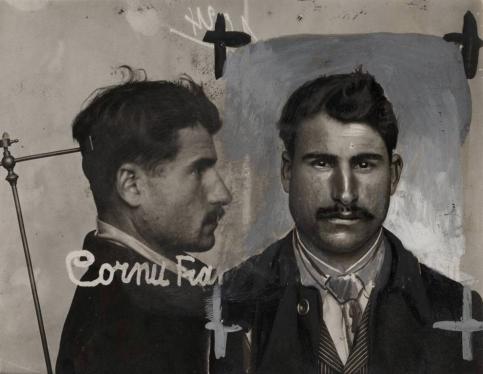

The technical quality of the images had to be sufficient to establish precise points of resemblance and to ensure it was possible to produce a large number of images on a daily basis. The Bertillon system or ‘Bertillonnage’ triumphed at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1889 and was rapidly adopted across Europe, Russia and the United States. Between 1885 and 1914, legislation against recidivism in France would lead to more than half a million people being put on file. As soon as the system appeared, however, Bertillon’s wrongful identifications were denounced and the possible dangers and abuses of such a system were pointed out. Its errors and imprecision, as well the specific form of the mug shot, soon became a subject of reinterpretation as artists such as Mac Adams gave a new twist to the subject by making use of the specific codes of the genre to question the spectator’s world view, the play of appearances and the ambiguity of the photographic image when confronted with reality.

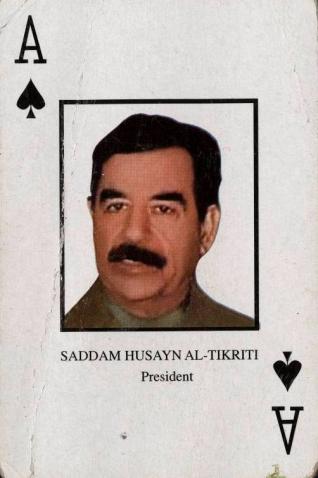

A source of scandals

No less than a cultural phenomenon, police identification photos were the subject of enthusiastic interest from the press as soon as they were invented. It wasn’t long before mug shots, even if their main function was to assist the police in their investigations, were nonetheless used to illustrate news items in newspapers such as Détective

, Le Magasin pittoresque

and L’oeil de la police

… At the end of the 19th century, a current of sensationalism overwhelmed the press, fuelling the imagination of readers in the same way as detective novels and reinforcing the credibility of the police forensic department.

A securitarian utopia

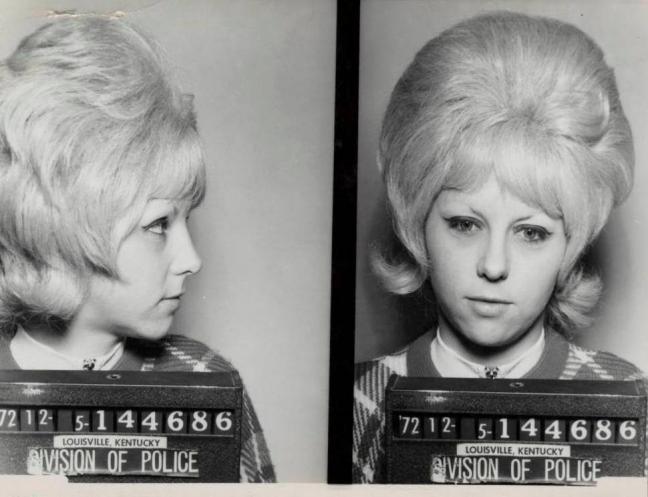

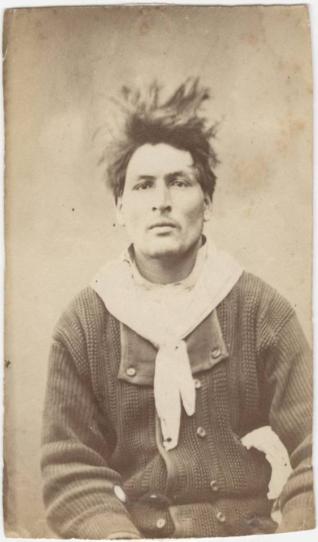

The arrest photo can be traced back to the origins of photography and, if some people recommended its use primarily to keep track of criminals and record repeat offenses, putting people on file was for a long time mainly limited to minorities who were considered dangerous with the aim of keeping certain members of society under surveillance. The visual identification of certain categories of the population who were a cause for concern – foreigners, travellers, bohemians, drifters and criminals – because a new and vital question for many European states. According to Bertillon himself, the process usually reserved for criminals could also be applied to ‘professional’ or ‘ethnic’ types. It was in this context that in 1912, a system of identification was instituted in France that saw the elaboration of an anthropometric card for nomadic populations in which Alphonse Bertillon took an active role. For the very first time, populations judged solely for their chosen lifestyle were obliged to carry a document that not only stigmatised them, but also legitimised their exclusion from the national community. It wasn’t until June 2015 that the French parliament voted the abolition of the ‘livret de circulation des gens du voyage’ [ special permit for travellers ] whose origins can be traced back to the identification system of 1912. Migrants, residents of colonies and occupied territories and prostitutes…Other populations which were conspired to constitute a risk were also subject to large scale registration operations, always for the purpose of control and social discipline.

A step sideways

Sometimes however it is out of the very context of surveillance and control of the population that an act of resistance is born, a step sideways that lets individuality and personality show through, and reveals the individual’s disapproval of the standardisation of a group. In the middle of the Algerian War, when the photographer Marc Garanger [ who was a soldier at the time] had to take the photos of women who were forced to remove their veils, or when Virxilio Vieitez took the portraits of the inhabitants of villages in Galicia in Spain under the reign of Franco for identity cards that had become obligatory, the process used and purpose of these images were not supposed to leave any doubt as to their message and future use.

And yet, the serious faces of the subjects, the jewellery and clothes they chose, the expression in their eyes and the meaning it conveyed and finally the photographic gesture itself are like interstices into which the unexpected, as well as a certain form of revelation can slip and transcend a system that is intended to be cold, rigid and scientific. Sometimes out of this highly standardised system, a whimsical and out of place gesture is born. One example is the actions of the Paris Vice Squad which, on May 4th 1990 during the arrest and expulsion of 800 transvestites from the Bois de Boulogne, took mug shots of the transvestite prostitutes, most of whom were Brazilian. To this first official image, they added a second portrait with a twist, a close-up in which the subject of the photo was free to pose for the camera as they pleased, with an attitude and expression chosen by the model himself that shifted the process giving it a whole new meaning and intention.

Exhibition co-produced with La Chambre Strasbourg, the collections of the musée Nicéphore Niépce and Ivan Epp, a private collector from Strasbourg