Jean-François Bauret :

perceive, receive

February 14th

… May 17th

2020

Opening Thursday February 13th

at 7pm

Curator: Sylvain Besson, Musée Nicéphore Niépce

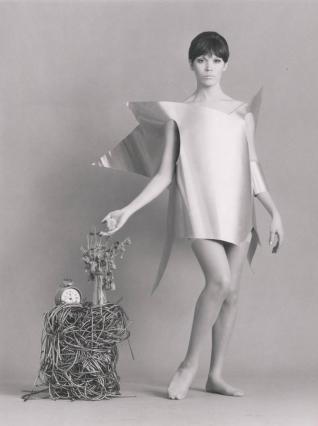

When Jean-François Bauret’s career began in the late fifties, anything was possible for a young, self-taught, enthusiastic, attractive photographer with plenty of connections. It was the time of the Trente Glorieuses, post-war reconstruction was ongoing, advertising was booming and sexual freedom was just around the corner. Jean-François Bauret spearheaded photography in advertising and, in his own way, can be said to represent half a century of the short history of photography.

The musée Nicéphore Niépce acquired the Jean-François Bauret archive in 2016. Three years of inventories, digitisation and research by the museum’s team have made things very clear: Jean-François Bauret was a prolific and transgressive advertising and fashion photographer; he was also an artist and portraitist truly of his time.

The size and diversity of the archive is rare, and it shows the work a photographer who cannot be reduced to two flashy scandals and a few series. This exhibition, entitled “Jean-François Bauret: Perceive, receive” proposes a retrospective of the artist’s career in almost four-hundred and fifty photographs. For the first time ever, the photographs, selected from the four-hundred thousand in the archive, will include both paid commissions and artistic pieces by the photographer.

Scandalous? Subversive? Modern? Trailblazing? Iconoclastic? Self-indulgent?

Showing Jean-François Bauret’s work is a challenge today as, while he was a photographer very much of his time, it would be almost inconceivable to show some of his nudes, were they to be shot today, even though they are what made his name between 1970 and 2000.

Jean-François Bauret, like so many photographers, was first and foremost a craftsman. When the medium was undergoing a transformation, he covered almost every genre. He managed to combine professional paid work with his artistic output, but there was such an emphasis on the latter that his commissioned work was often forgotten about. However, we must point out that his personal work makes up a tiny part of his archive.

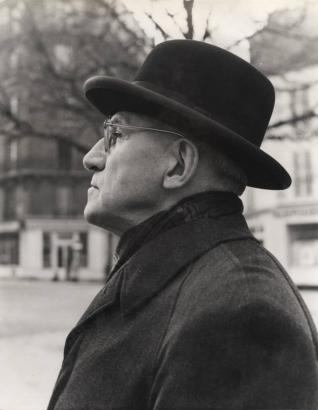

His early work included portraits of artists such as Bram van Velde, Pierre Alechinsky and André Lanskoy. The painters, sculptors and musicians photographed were all under the patronage of his father, Jean Bauret, an industrialist, patron and collector from the Lorraine region. These intimate, edgy portraits, were often taken in the artists’ workshops and his attentive eye and narrative sense as well as his talent for lighting gave these portraits a timeless feel.

However, Bauret’s career really took off when he met the interior designer and stylist Andrée Putman. She was responsible for his early commissions for the magazine L’Oeil and the Prisunic stores. Thanks to his name and his network, the advertising jobs came flooding in. With the help of his wife, the painter and collector, Claude Bauret-Allard, who acted as both his assistant and model, Jean-François Bauret was at the forefront of the genre’s renaissance. His compositions, inspired by Claude, were a hit. The body (often Claude’s), either blurred or against the light, was omnipresent in his early work. The poetry of the compositions took the chill off the articles being advertised which included everything from beauty products to sheets to spaghetti…

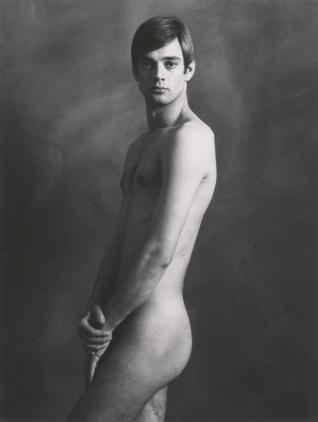

Bauret soon established himself as a photographer but two campaigns for Publicis had a huge impact and were to raise his profile suddenly. Bauret insisted on using a naked man for the 1966-1967 campaign for Sélimaille, a men’s underwear label. In the Spring of 1970, he shot a naked pregnant woman and child for Materna. Feedback to the advertisements was as heated as the audacity of his approach, as never before had any brand used an entirely naked man or pregnant woman in a campaign. The reactions to both campaigns were negative and violent. They brought in a sea change in advertising in the sixties, showing the growing importance of photography, and heralding a new way to use the body to sell products. Bauret soon made a name for himself as a subversive and provocative photographer.

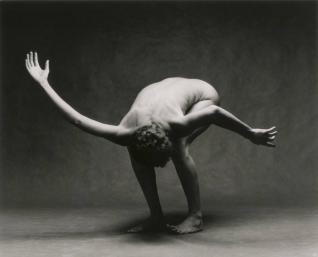

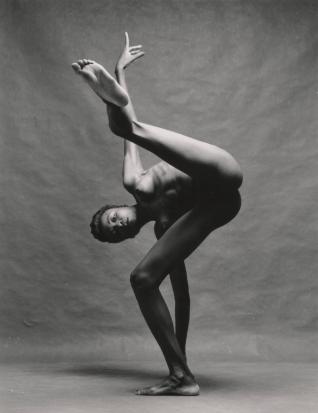

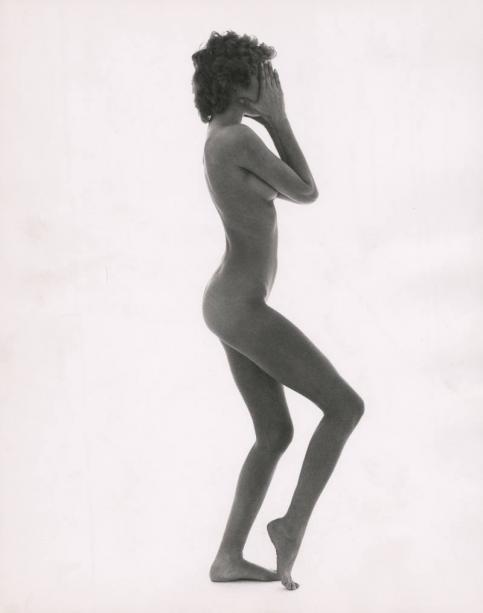

Both campaigns were based around a nude portrait, which was to become a veritable obsession for Jean-François Bauret. His shots were like an inventory of the body, full-frontal, taken in the studio on a neutral background and with subtle lighting. “Beauty” didn’t come into it, he revealed bodies with no artifice, as he felt this was the only way to get a to the subject psychologically.

Jean-François Bauret added to the renaissance of the portrait and the photographic

nude, far from the academic poses of the 19th

century, the daring angles of the New Vision and the ambiguous sensuality of some of his contemporaries.

As early as the seventies, Bauret began to show and gain recognition for his artistic work, but he never abandoned the bread and butter side of things. He shared his work through Photothèque , maintained close links with big magazines such as Jour de France, Enfant Magazine, Télérama, Actuel and Jardin des Modes and with brands like New Baby and Air France and remained determined to stick with the less artistically rewarding but highly lucrative aspect of his job.

Baudret was truly a significant photographer. He showed his work frequently with 62 solo exhibitions and 57 collective ones between 1956 and 2008. Baudret also shared his knowledge and experience with amateur photographers through courses and workshops, holding a total of 41 between 1982 and 2005 and he worked tirelessly to raise awareness for the medium and keep it in the public eye, notably setting up the website photographie.com in 1996.

He was a man of few words who turned into a chatterbox once he got into the studio, and he left behind him many images but wrote little. What was Jean-François Bauret looking for? And was he even looking for something? Was photography nothing more than a job for him, or was it a pretext? The sheer profusion of his work leaves the unfinished feeling of his attempts to grasp something, his inability to capture the nudity that was the last path to abandonment.

![Jean-François Bauret Proposal for Mitoufle advertisement 1966 Silver gelatine print on paper [contact sheet] © Jean-François Bauret Jean-François Bauret Proposal for Mitoufle advertisement 1966 Silver gelatine print on paper [contact sheet] © Jean-François Bauret](/var/ezflow_site/storage/images/exposition-en/futures/bauret/bauret-amanda/52275-8-eng-GB/bauret-amanda_2_colonnes.jpg)