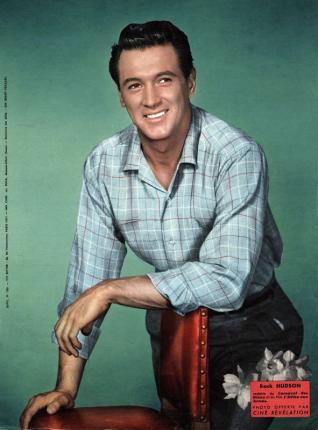

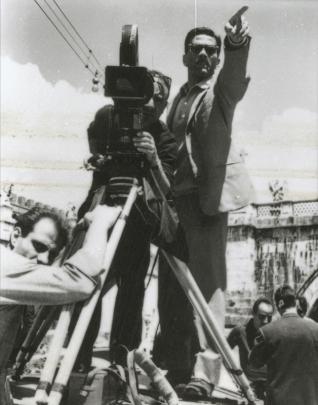

The tie that binds photography to cinema is self-evident. Film feeds off photography. It constitutes the ultimate progress applied to the image with the addition of movement, then sound; the cinema outbid photography in spectacular terms. Film was popular from the start – unlike photography which remained inaccessible to the general public for a long time – and it spread its hegemony very rapidly, claiming its « superiority » over the non-moving image. However, film could never shake off the essential role played by the photographic medium in its commercial success. Promotional photos in the foyers of cinemas and stills from the shoot that revealed the inner workings were all aimed at informing and inciting the public to become customers. So, paradoxically, the cinema found itself dependent on the fixed image and ordered photographic narratives in magazines or on walls.

Cinema is still paying off its debt to photography. It emanates from photography but thought to break its ties from the poverty of the fixed image, regarding it as the origin, an antique that one can’t throw out but can consign to the attic. What if photography was detrimental to cinema? The photogram or still was thought to be incapable of rendering the effects of the edit as it disregarded « filmic time ». Eisenstein compared « beautiful » stills to « a disjointed muddle of beautiful phrases

»! Need we remind you that both media shared and still share common equipment and modes of broadcast? Even though it tried to emancipate itself from the simplicity of the photographic object, cinema had to eventually admit, it can’t do without photography. Photography ensures its existence with promotional shots before the film comes out or at the release, and throughout a film’s life cycle. It accompanies cinema, giving it coherence in the media and establishes it in the magazine and book universes.

The relationship between the two, that some have deemed testy, took on an original and complementary character at the end of the twenties thanks to the development of heliography. Publishing houses, but also cinema producers saw the possibility of ensuring the launch and advertising of film through the establishment of specialist magazines. Inversely, the unprecedented character of filmic narration largely led to the reinvention of photography and magazines at the end of the First World War.

In the end, these two moments in the history of the mechanical image reveal complementary meanings and provide different types of pleasure.

We now need to think of the still, not as a simple promotional illustration, but as a distance, an « extra » that reveals what we don’t see on the screen.

Curator: François Cheval

Research: Emilie Bernard, Marie-Odile Géron

Scenography: Christelle Rochette