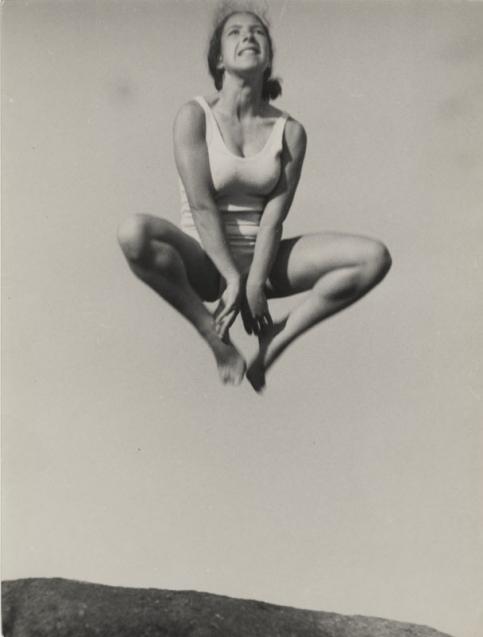

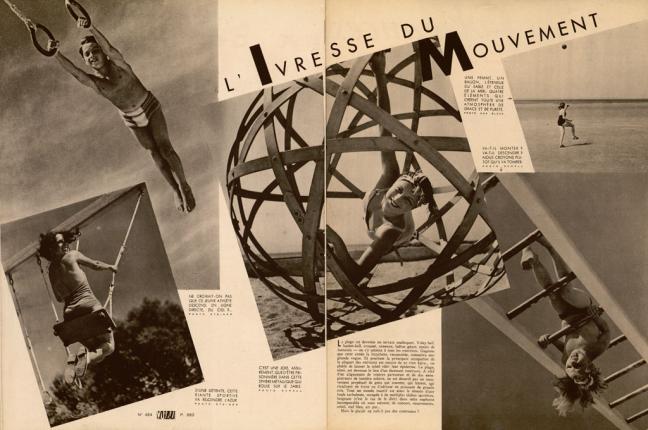

It is misleading to take multiple representations of the body to be an offshoot of the photographic portrait. The portrait is a tentative approach at a psychological profile. The photographed body captured directly is a manifesto. The body needs only itself to put on a display. The portrait relies on the decor, an accumulation of attributes to bolster its meaning. Thus we go from an image laden down with objects and signs, to a stark image that focuses on the consequences of effort. The quest for movement that adorned the first photographic magazines shifted to make way for a sculptural aesthetic. While, to begin with, Marey and Muybridge were useful in the understanding of movement, photography in the thirties took on the traits of the ancient arts of sculpture and the nude. We would be mistaken to see this evolution as a passage from the eugenics of physical education to a recognition of the intimate. The social and collective practice of sport dispenses with nudity’s air of indecency. The naked body loses all its erotic meaning in favour of a societal ideal.

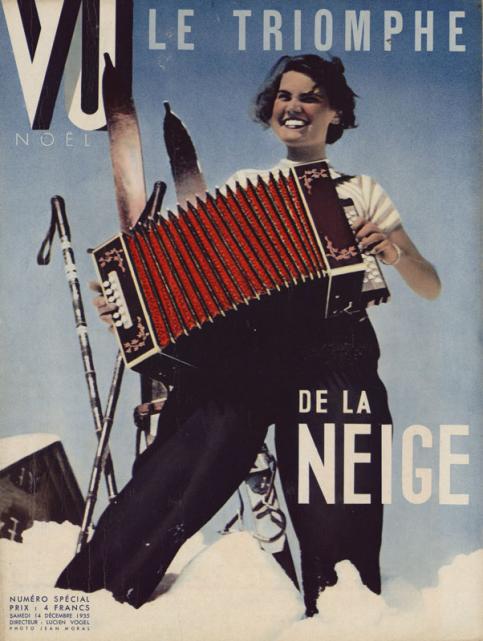

Gymnastics was initially a social practice reserved for the “elite”. It was part and parcel of the art of self-representation. Through the conspicuous exhibition of a straight-backed body, photography celebrated a way of life by rejecting the concept of “letting oneself go” and giving in to temptation and pleasure. The new “aristocracy” of the inter-war years, through the quest for the perfect movement, saw sport as belonging to a certain modernity that didn’t involve individualism, taking their inspiration from eugenics. Performance took over from well-being and life in the fresh air was nothing but a continuation of the prowess seen and admired in magazines.

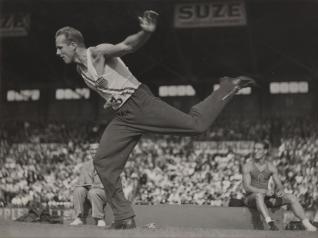

A wide range of new magazines displayed the geometry of the body in their centre-folds. Physical education and health manuals were reduced to restricted circles. The idea was no longer to manufacture bodies that were ready to fight the barbarian (the German neighbour) and asceticism was not behind the new idea of the body. Sport photography was evidence of the power and wealth of a nation. Parallels with this new sensibility, the shift from a lifestyle to the exaltation of sporting exploits can be found in the dynamic of the press of the time and, in particular, with the development of reproduction techniques. The press latched on to the photogenic nature of the sporting body that was in fact represented as a demi-God, the heir to the Homeric hero, taken by surprise in close-up.

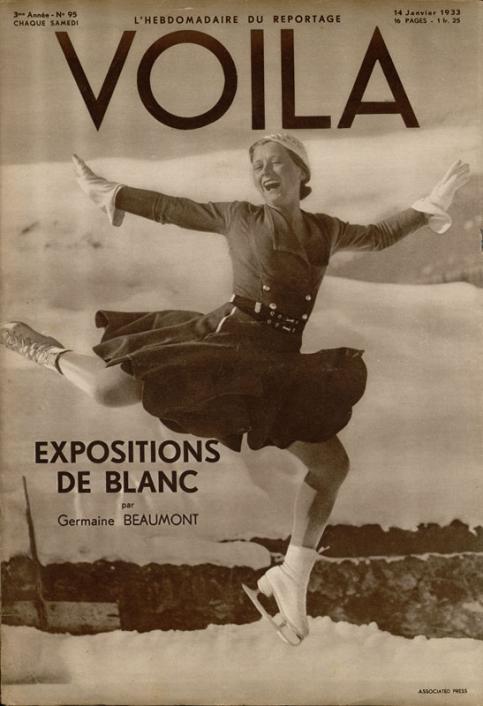

Sport and photography came together to define modernity. They shared the idea of a moment shared and its instantaneous nature. Photography went way beyond film as it was precise and close to the action. It transposed a moment the very nature of which was ephemeral. What in fact the magazines from the thirties invented was the transfiguration of a simple act into an epic poem. The mechanical image, supported by praise-filled text, transcended the event to turn it into a veritable collective phenomenon.

As early as 1919, those who were referred to as the “preparatists” wished to contribute to the reconstruction of France. In 1918, the power and good health of one people overcame the power and good health of another. Nevertheless, the crux now became the exemplarity of the winner and not just principle and virtue. The spectacular character of photography now required more than just bodies gambolling in picturesque landscapes. It needed the spectacular theatricality of the stadium so that the body could express its dramatic qualities and provide support for the myth. Photography thus became an essential component of a totalitarian ideology.

The value thus accorded to the body required the de-realisation of the subject, the other materiality of the corporal substance. Effort was a symbolic charge. The image of the champion’s anatomy was raised to the level of the sacred. As an unperishable envelope, it integrated into the long history of the West. However, the body of the “other” was thus dehumanised, ready to be sacrificed. The magazines of the intelligentsia and in particular “Vu” did not hesitate to associate the used-up body of the working man with the century of industrialisation. The body no longer belonged to individuals. The body of photographic modernity became a social construction, a piece of fiction.