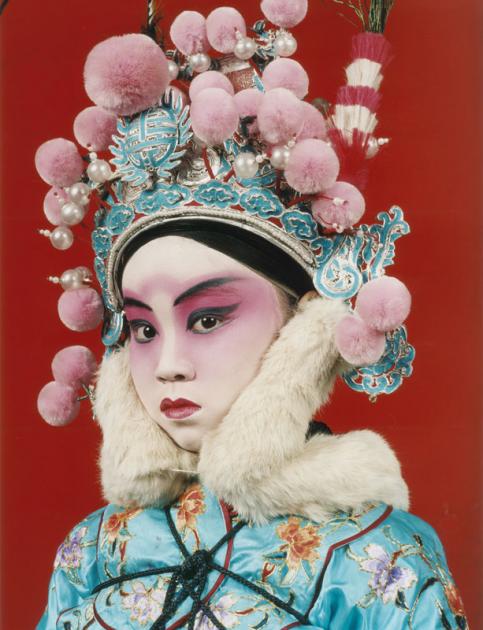

Military uniforms, work overalls, ice-skating and ceremonial costumes form the basis of Charles Fréger’s photographic work. The strict protocol to which he adheres in the creation of his portrait series goes way beyond a simple inventory. The initial impression of documentary work is misleading. What we have are actually psychological portraits, where each subject affirms their membership of a social body through their uniform.

The musée Nicéphore Niépce has been an ardent supporter of Charles Fréger for many years and is now showing his first big retrospective with over one hundred images.

Year after year, the obsession persists, compulsively. Countless exhibitions, accompanied by impressive catalogues and books have succeeded one another, and Charles Fréger provides us yet again with a new and always unusual series. Enriched with a knowledge of sociology and anthropology, we think we know everything about human beings and their unbridled taste for ceremonial dress and accoutrements of all kinds. And then with Wilder Mann, an extravagant assembly of men born before God was invented assuring us of the madness of humanity whose instruction will never end.

It has something to do with an inventory, or is quite like one. But in order to found a reasoned catalogue, the artist would need to use a typological method. And is this really possible? Can one truly isolate the predominant factors in each series? In other words, does the uniform maketh the man?

The images themselves are too complex for the reality to be that simple. Charles Fréger is an observer who places us right in front of real phenomena. He provides us with his considerations. The operation is characterised by a will to reference all of the problems of taking a shot using a technical grid. It also determines a concrete method aimed at outlining the characteristics of each group studied. Paradoxically, the idea of a typology collapses as this photography looks neither for a cause or an explanation for the real, concrete man.

The Human Sciences have perhaps established a logical link between Japanese sumitoris, Finnish synchronised skaters, « French » legionnaires and Royal Highlanders. The feeling of belonging to a group, the solidarity that exists between age-groups or integration rites has not escaped « scientific » analysis. Charles Fréger’s point of view is very different. One after the other, his photographic series form a coherent discourse, an underlying thread through the madness of the body and the social.

Each episode is a singular fact built according to the photographer’s own set-up. Far from a simple shot, we are close to the absolute in terms of description. Charles Fréger has been a sumo wrestler, he has ice-skated in Helsinki, and he has even joined the army and buttoned up his spats.

By ignoring the spectacle of the uniformed parade, the ceremonial aspect of these situations, we realise that the only real event is a fake gathering, a private ritual, for the photographer’s use only. So let us leave aside all references to August Sander, to German photography, to the New Objectivity, to serial references and let us examine in depth the real issue, the photographer’s obsessions.

Charles Fréger unilaterally accentuates the point of view; he links together a multitude of isolated phenomena the finality of which is above all aesthetic. He is not formalist, but he is the first to be fascinated by the scene he organises. The backgrounds are primordial. They are not just there to highlight the model; they project the idea of a luxurious iconography, a collection of preciously preserved chromos. We could reproach him for this. But, he respects the spectator too much, delivering a flow of cultivated information, text and references. This surplus of words throws no light on the issue and only admits a sense of marvel and enchantment for these tableaux of postures and times past.

There still are territories where man has found himself and has gained in terms of harmony and perfection. This world rejects shadows and gives itself without hold anything back. Does this mean that we can’t find any imperfections or anything bizarre in these portraits of human beings?

The perfectionist dramaturgy procures a sense of immediate satisfaction. Everyone gets obvious enjoyment from the geometry, the shine and the palette of colours. What an illusion is this resolution of the tensions and contradictions of the world, the artifice of a place without roughness! The anxiety is evident on all of the faces. We catch a glimpse of an immanent danger, an expectation that the perfect organisation of the second skin is the only thing that could upset things.

There exists, between the photographer and his models, a community of feeling, sensations and fears. The photographer is apprehensive of failure or shortcomings, the consequence of which is the creative void. This is why he hunts down his fellow humans in their most accomplished form. He is a despotic photographer, imagining himself at the head of the « Fréger Guard ». With his photographic machine, an instrument of social control, he orders or feigns a coding of the body and desire. What he does is the opposite of the documentary, moving definitively away from descriptive photography; Fréger’s work reveals itself to be the most accomplished form of schizophrenia in the modern world, an illusory and obsessive attempt to free oneself from tension to better capture mood swings, anguish and outbursts.

François Cheval