This year, in partnership with the Centre national des arts plastiques

(CNAP), a number of the musée Nicéphore Niépce’s temporary exhibitions will present a selection of work from the Fonds national d’art contemporain

, France’s largest contemporary art collection that is managed in France and abroad by the CNAP.

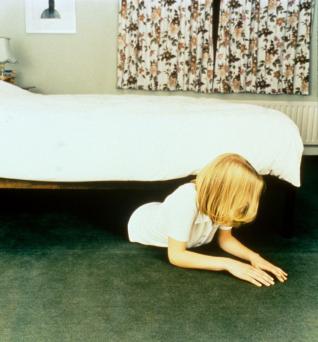

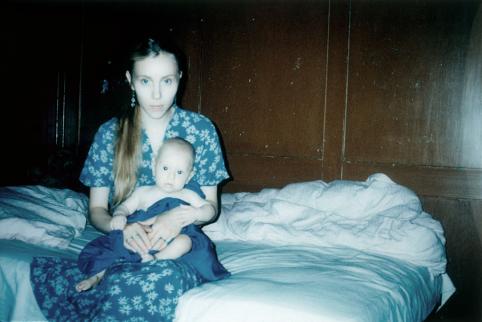

For this, the first partnership, the musée Nicéphore Niépce has selected work by contemporary women photographers Valérie Belin, Elaine Constantine, Sarah Jones, Marylène Negro and Annelies Strba.

« Close, merciless shots depict a severe tableau of inanimate objects and people. In what seems to be a recent but broadly shared approach, women photographers have started, through diverse means, depicting a world where lies take precedence. Feelings and qualms are dispensed with by using an absolutely emotionless descriptive model. Photographic situations are no longer based in the real dispensing with this useless rapport with the demonstrative. This generation of artists has no time for topography and statistical crudity, or for romantic exaltation. What we have been seeing lately is a photography that has thrown off all simplistic psychology. The emotions of young girls have been gotten rid of, love stories forgotten. We are no longer invited, despite ourselves, into unmade beds, and interiors that just need a little tidying. This, sometimes sensationalist, often inappropriate intimacy has been replaced by work whose common denominator seems to be oddity.

Now, affirming oneself as a photographer and a woman means going beyond appearances. Getting back to the essence of things, trapping its reflections, measuring its import, which means a refusal of the anecdotal and the accessory. We have a number of them in our midst. The objects seem like living things and the subjects are reified. This makes us unusually tense. The photographer accepts and plays with this malaise. We are trapped; these simulacra, both objects and characters, contemplate us as if petrified. They are distant and elsewhere, and are disconcerting as they are disenchanted representations of ourselves.

Photographs of surfaces and reflections, their damaging presence reflects the sad original, the postures and fabrications of this tragic farce.

These non-portraits, these objects made of uncertain material look us up and down impassively, like phantoms of reality.

Photography has a debt towards women. In the twenties and thirties they appropriated this new instrument as an act of emancipation. They became part of the wind of change, all the better to carry it.

Immersed in the real world, active in studios and magazines, for about ten years their photos accompanied all fights for freedom.

These explorers of modernity followed the specifics of the machine in all its hidden corners and depicted the female form in all its detail.

What we propose today follows the trail of the photographic “acts” of these free and independent women.”

![Photograph[e]s, vue de l'exposition Photograph[e]s, vue de l'exposition](https://en.museeniepce.com/var/ezflow_site/storage/images/exposition/exposition-passee/photograph-e-s/photographes-vues-de-l-exposition/8383-1-fre-FR/Photographes-vues-de-l-exposition_illustration_article_left.jpg)

![Photograph[e]s, vue de l'exposition Photograph[e]s, vue de l'exposition](https://en.museeniepce.com/var/ezflow_site/storage/images/exposition/exposition-passee/photograph-e-s/photographes-vues-de-l-exposition/8384-1-fre-FR/Photographes-vues-de-l-exposition_illustration_article_left.jpg)

![Photograph[e]s, vue de l'exposition Photograph[e]s, vue de l'exposition](https://en.museeniepce.com/var/ezflow_site/storage/images/exposition/exposition-passee/photograph-e-s/photographes-vues-de-l-exposition/8385-1-fre-FR/Photographes-vues-de-l-exposition_illustration_article_left.jpg)

![Photograph[e]s, vue de l'exposition Photograph[e]s, vue de l'exposition](https://en.museeniepce.com/var/ezflow_site/storage/images/exposition/exposition-passee/photograph-e-s/photographes-vues-de-l-exposition/8386-1-fre-FR/Photographes-vues-de-l-exposition_illustration_article_left.jpg)

![Photograph[e]s, vue de l'exposition Photograph[e]s, vue de l'exposition](https://en.museeniepce.com/var/ezflow_site/storage/images/exposition/exposition-passee/photograph-e-s/photographes-vues-de-l-exposition/8387-1-fre-FR/Photographes-vues-de-l-exposition_illustration_article_left.jpg)