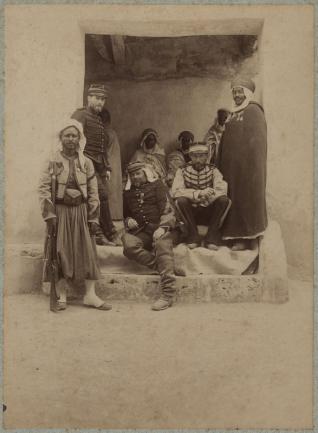

The first part of this exhibition is dedicated to a presentation of a selection of archive photographs that span from the military colonisation of Algeria to the events of the nineties. The “Algérie, clos comme on ferme un livre ? / Archives” exhibition is made up for the most part from the musée Nicéphore Niépce’s own collection. It helps us to understand the contrasted and unique situation that was the French colonisation of Algeria, through an original collection of over 130 documents that form the basis of the historical premise.

Too far, too near, France never knows how to approach Algeria and this is more than evident in photography. There is no end to the images of the country; home-produced images are another question. Here, as elsewhere, photography is a question of viewpoint. The early images are military, depicting the colonial troops. The shots in the early albums paint a picture of the pacifying and emancipating role played by France, France the great. The strictness and serenity incarnated by the mehara

and colonial doctor.

At the time, military men liked to depict themselves as ethnologists, geographers. But the pacifier was above all shown to be a town builder; they « built roads, drained swamps, put down the indestructible foundations of our France

d’Afrique

»: Marshall Franchet d’Espèrey.

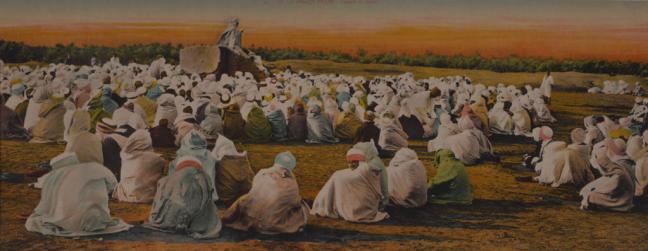

In that which is nothing but a succession of changing backdrops, of rivalling tribes, the French soldier unified and transformed a country divided. From the green reefs of the Constatine cornice to the dunes of the desert, to the fertile plants of the Mitidja, photographers actively participated in the myth of the « Nouvelle France ». They churned out contrasting images and forced light into the shadow of the Kasbah, foisting the modern on to the picturesque.

This old country, thanks to the coloniser, went back to its Mediterranean roots. The archaeology and photography remind us of other origins than Islam. Guides, brochures and books endlessly tell is of its classical heritage, this shared past that unites both sides of the Mediterranean. Photographic publications consolidate the idea of a greco-latin culture that predates Islam and shows statues of Bacchus, Esculape, theatres and temples in ruins.

In the end, this astute but fragile mish-mash must give way to local colour.

The colour photographs in surreal colours depict a generous and orientalist Algeria; oases and palm trees on the edges of the deserts and dunes; a desert peppered with extras from adventure films. It was the time of the French Foreign Legion, the goumier, heart-felt, honest characters as opposed to the image of the petty criminal hidden in the depths of the Kasbah.

Here, in the wandering side streets, there lived a world we know exists but that managed to escape the eye of the photographer. The small people of Algeria are summed up in a few stereotypes; the underage prostitute, the beggar child, white, veiled shapes fleeing the photographer’s gaze. The Algerian city, with the picturesque removed, regains its element of danger and affirms its resistance to « civilisation ». But the modernity and fortune of Algeria were written by French hands. The 1950’s postcard proclaims as much. Everything that was done, produced, built on this land was due to the colonisers, not the natives. The «Nouvelle France» so praised in images is but a carbon copy of the motherland.

Chapter by chapter, the illustrated history of Algeria took a collection of beautiful images from photography, well chosen documents that, by hiding the contradictions of colonisation, contributed to the general ignorance surrounding the legitimate claims of the Algerian people.

The images transmitted by wire were to be a violent reminder to metropolitan France of the complex and brutal nature of colonisation.

Under the watch of the foreign press, demonstrations in support of French Algeria degenerated when partisans of the F.L.N called for a Muslim Algeria. Things accelerated and shifted in the war that did not speak its name and chose its image: « felon » generals, bloody faces in the streets of Paris, the fleeting silhouette of Krim Belkacem in Evian, the ceasefire, independence. Images of joyful crowds.

So, is the chapter closed as the Algerian national anthem claims?

A collection of ID shots of civilians who disappeared in the nineties call this into question.

Independence lasted for a moment, it was but a prelude to other, equally bloody battles, a continuity of the violence meted out to the Algerian people, from the « expeditionary colonisers » of General Bugeaud and the carnage of Sétif to the massacre of the harkis.

« Clos comme on ferme un livre? », a history in pictures that isn’t one; a collection of shortcuts, disjunctions, choices made to open another book of images.

François Cheval

Curator of the musée Nicéphore Niépce