« Photography for another world » presents experimental photography by Charlotte Perriand (1903-1999), better known for her work as a designer and as a collaborator of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret.

As early as 1928, Charlotte Perriand was using photography as working tool in furniture design, then as a source of inspiration for her research into shapes and materials… She is one of the first to have used photomontage on a grand scale in interior design. She was hired by the Front populaire to create huge political and educational murals where she used her innate sense of narrative to depict social change and manifested her commitment to left-wing politics.

The exhibition at the musée Nicéphore Niépce is dedicated entirely to her photographic work. It includes a number of original prints, some reconstitutions of her friezes to scale and a series entitled « L’Art brut ».

The twenties saw a change in the status the photography as it came to incarnate the very essence of modernity. The avant-garde took it over and worked it over to create a new artistic language, banishing the picturesque forever in favour of graphic novelty. The era was fascinated by technique and the machine. The world was being rebuilt, but according to rational rules in order to attain perfection.

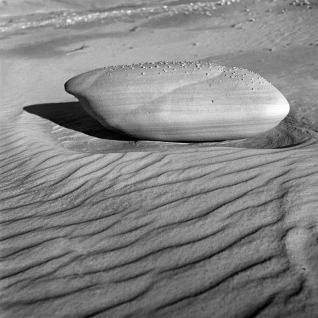

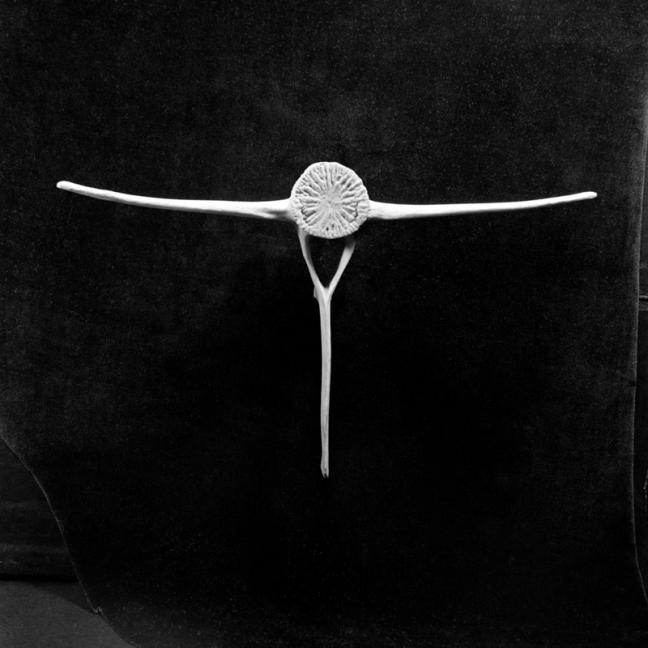

It was in this « state of mind », that of the « aesthetic engineer », that Charlotte Perriand made her first pieces of furniture. As a young designer and architect who worked with Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret from 1928, she used photography intuitively, recording shapes that caught her eye: the metallic structure of a bridge, the netting of fishing net, a pebble, all became sources of inspiration for the design of her chairs, tables and shelves.

Charlotte Perriand maintained a mystical relationship with nature, a carnal relationship with raw matter. In the thirties, she collected objects found in nature in the company of the artist Fernand Léger: bones, rocks, pieces of wood whose beauty caught her eye, « objects with a poetic reaction » according to Le Corbusier. « Our backpacks were filled with treasures: pebbles, lumps of old shoes, bits of raggedy wood, shaped, sculpted by the sea (…) it was what we referred to as l’art brut » . By photographing objects on a neutral background, Charlotte Perriand highlights the purity of the lines and the power of the materials. « L’Art brut » espoused a belief in the primal beauty of the world and modified modern man’s relationship to what can be felt.

Charlotte Perriand travelled around Europe accumulating images that constituted a repertoire of shapes and ideas. At first an adept of starkness and the aesthetic power of the functionalist architecture dear to Le Corbusier, in 1935 Charlotte Perriand shifted toward a functionalism of circumstance, to a modernity that was anchored in the human, taking poetic, geographical and cultural realities into account.

Adapting architectural vernacular to the countryman’s way of life was just as interesting to her as the monuments of ancient Greece. She went against the tide of the contemporary avant-garde in considering man, whose postures and attitudes she observed, as the basis of all reflection on architecture. The singularity of her work comes from the way in which she took the human into account; by observing life and nature, notably through the photographic lens, making architecture serve the body.

This humanism naturally led her to militate against the plagues of her time: unhealthy living conditions in cities, poverty… Photography enabled her to express her political convictions. « One can make photography say anything, by cutting, shifting it around; it is an accessible, comprehensible and effective realist form of expression. »

She innovated by creating huge photographic murals from photomontages. To support her militant stance, she used her own photographs but also those from press agencies or photographer friends such as François Kollar or Nora Dumas.

Her mural entitled « La Grande Misère de Paris » created in 1936 for the Salon des arts ménagers de Paris caused a scandal a few months before the Front Populaire came to power. Over a space of almost 60 m², Charlotte Perriand denounced the deplorable living and health conditions in Paris. Completely ignoring the laws of perspective, she overlapped images and points of view. The accompanying texts and figures supported her photographic stance.

* [La Grande Misère de Paris was destroyed at the end of the 1936 exhibition, but 80% of it has been reconstituted by the laboratory at the musée Nicéphore Niépce to the original dimensions using original prints and negatives. The colouring and insertion of typography were done by the team at the Zurich Design Museum. ]

The Front populaire commissioned other murals from her to promote the reforms of agricultural policy. Charlotte Perriand created a mural for the waiting room of the Agricultural ministry in 1936 and the Pavillon du Ministère de l’Agriculture in 1937.

The accumulated images glorify agricultural and industrial France, a political sign of the wish to unite the peasant and working classes in the same struggle for progress.

Charlotte Perriand’s photomontages illustrated man’s place in the city and the world of work, denouncing the injustices and ravages of capitalism and the absence of social policy in the country. Her photography became the visual tool of a documented discourse aimed at the masses. The stance was in line with an era that magnified industry, rural life, technology and nature in one felled swoop.