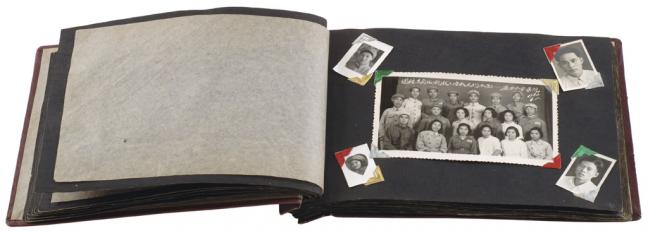

Family albums are a priori insignificant objects, just like the photographs they contain. In them, we expect to find the archetypal images of family life: births, celebrations, and maybe a few trips abroad… However, if we study them more closely, the way an album is created differs greatly from one to the next, from the choice of photos to their layout, as well as the rhythm of the narration. The musée Nicéphore Niépce has taken an interest in family albums for many years and has constituted a large collection through targeted purchases and donations. In this exhibition, the museum will try to determine what makes up a family album.

Once these polymorphous objects end up in a museum, their original function ceases to exist, their meaning is lost. Even though the chain has been broken and the stories scattered, the banality of the narrative is paradoxically transformed into a mystery that we try to solve. The most everyday event exerts a fascination over the viewer that is difficult to explain. Lineage creates a visual treasure hunt that is incredibly entertaining. Sometimes history surges into the frame legitimising our curiosity. Despite the fact that we are detached from the reality of the individuals involved, our interest in these albums today is eagerly fuelled by the intimacy of the images.

The definition of the family album may be quite formal – it is an organised collection of photographs stuck on bound pages – but the object itself in its diverse forms reveals itself to be much more complex: the album is a pictorial biography. It marks an important step in the history of self-representation: it was the first opportunity afforded to people to build a personal story, in a more or less idealised manner. The personality of the biographer – the person who places the photos in the album, classifying them and giving them titles – is as such decisive even if they are not the photographer. Family albums tell the story of their author and his or her close entourage, with the aim of preserving and handing on memories.

A game of society and appearances

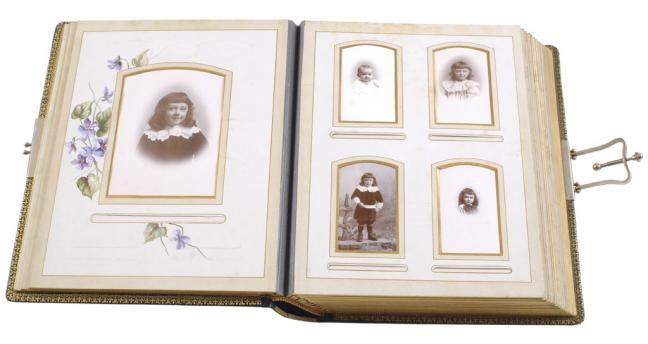

The first family photograph albums appeared in the 1860s. They went along with the fad for the portrait « visiting card », that members of good society had taken in bulk at the photographer’s studio to hand out to family members or social acquaintances. In the little pre-cut openings on the pages, one inserted these little card-backed portraits. The family was assembled artificially, even classified in the most conformist way possible. The narrative was limited to the more or less obvious ageing process of the protagonists, when they appeared at intervals throughout the album. They were a miniature and portable version of the gallery of paintings of ancestors reserved for the aristocracy until the advent of photography and they bore witness to the appearance of the bourgeoisie, a social class in search of recognition that happily juxtaposed portraits of “great” political or intellectual figures with their own representations.

Despite the freer format as opposed to the visiting card portraits and the changes in photographic techniques, the constitution of family albums remained a practice reserved for the elite until the start of the 20th century. The activity implied the availability of time and money, as is evident from the quality of the binding, but also the care taken with the layout of the photographs. Sometimes they were made by professional studios.

The generalisation of a practice: the shift to conformity

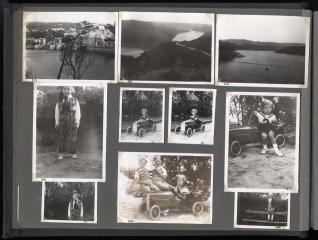

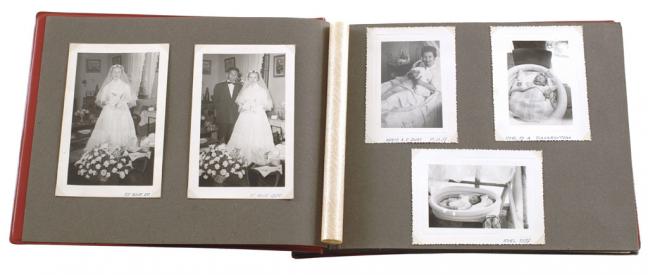

In the first half of the 20th century, the photograph became more a part of everyday life, becoming available to all social classes thanks to the simplification of techniques and a drop in costs. The big moments of family life were recorded by the camera and the images it produced became the guarantors of the memory of their author and his or her close family circle. The album enabled the organisation of memories, in chronological order unsurprisingly, sometimes with added notes or amusing titles. It brought the generations together artificially and froze the family structure in its pages. Photography became the proof of group cohesion.

Invariably, in the albums, we find records of weddings, baptisms, communions and other celebrations considered to be happy events. The birth of children and the first few years of their lives are also a central subject. Photography created the illusion of freezing moments that go by too quickly, while also providing proof of the growth and progress of the little ones. The family album depicted other happy moments, as insignificant as a Sunday picnic or a nap in the garden or as exceptional as a foreign trip. Some seem to be travel notebooks as they show proof of passage in dreamt-of faraway places.

Outside the family, the second circle

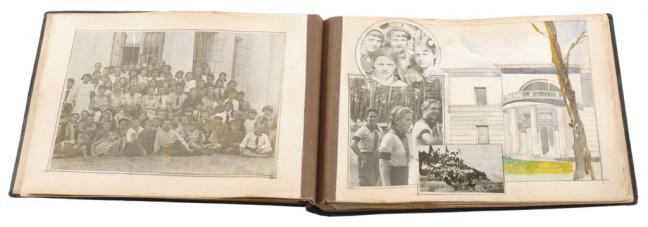

Few albums go beyond this stereotypical representation of the family unit. In the conformity of these pictorial autobiographies, individuality expresses itself sometimes through the opening up to a second close circle. The author then integrates photographs of close relatives, photos of friends, work colleagues, sometimes giving them their own full album. The social link thus lost its imposed, filial aspect and revealed the aspirations and temperament of the narrator all the more clearly. The album materialised the network of affinities and complicities that each individual created around him or herself throughout a lifetime, beyond the circle imposed by the family unit.

Curators :

François Cheval, Christelle Rochette, Anne-Céline Besson, Carole Cieslar, Caroline Lossent et Emmanuelle Vieillard

In 2005, the museum also produced the documentary entitled

« Familiarités, les albums de l’amateur » (Familiarities, amateur albums)

A film gleaned and composed by Michel Frizot and Cédric de Veigy

Length 45’

DVD French / English

On sale for 14€90 in the museum shop