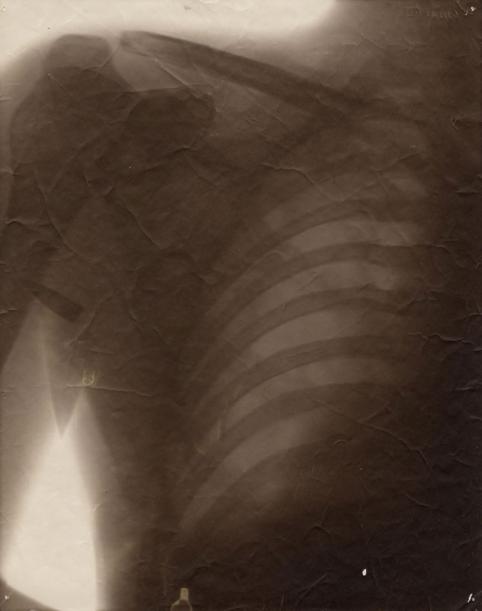

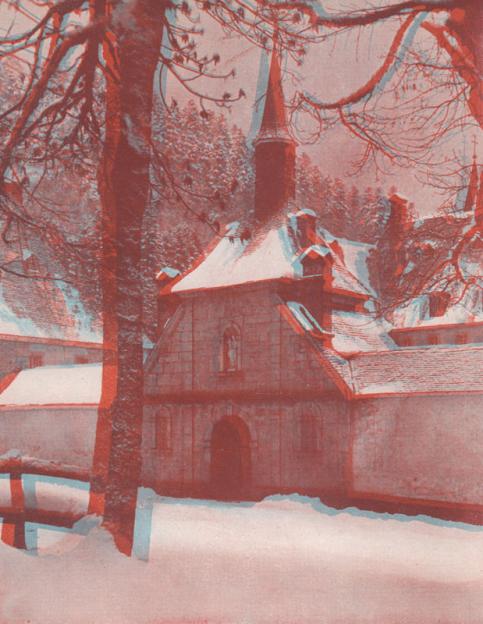

In the mechanisation of the image, the 19th century saw a means by which to improve the effectiveness of representation and in doing so, provide an ultimate explanation for everything. The camera was a way to see more and better: microscopic, aerial, satellite, radiographic and 3D photography… Man thus added to his visual capacities. He understood the universe better and was in a position to wield more power over it.

The camera gained its autonomy and engaged in a permanent race for progress. Today, it can switch itself on with a simple smile or movement. Technology produces the image, taking the need to master a process which had become too complex out of our hands.

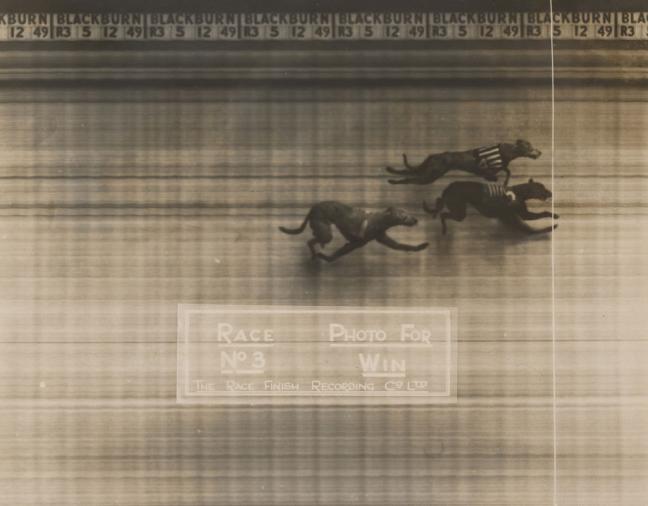

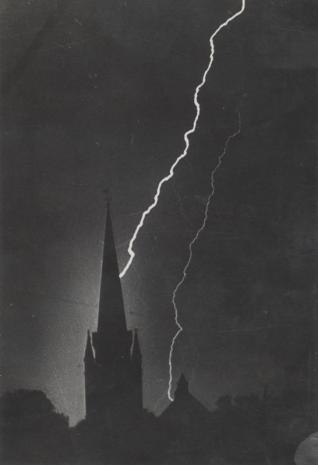

The quest for instantaneousness in pictures has been a constant since the invention of photography. Technical progress, the emergence of gelatine-bromide silver prints meant the time between taking the photo and the resulting photographic image got shorter and shorter.

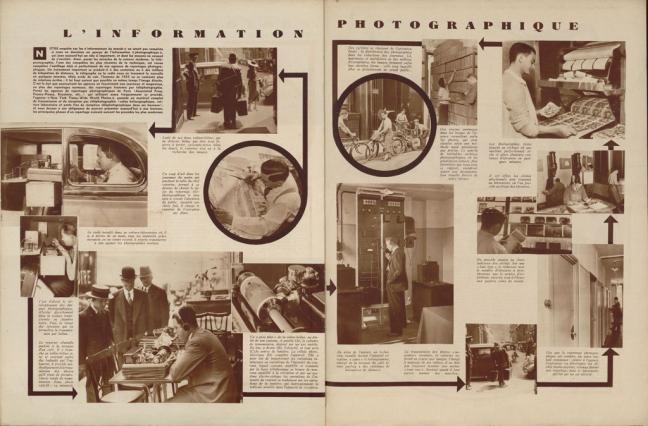

The elimination of the time span between the click of the camera and the actual photo has been the quasi-utopian objective since the start and it was finally attained with digital technology. Instantly sending the image through space was the other clear aim since the invention of the belinographer and is today possible through the internet and the smartphone.

Photography thus fulfils the universal fantasy of mastering time and space, and through it, the spreading of universal knowledge. The simultaneousness of the event, its capture, broadcast and reception is now the norm. This immediacy is an illusion. Confronted as we are with a continuous flow of « informative » images, we experience events live from all over the world without necessarily understanding them.

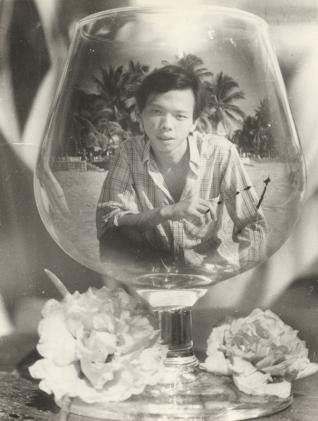

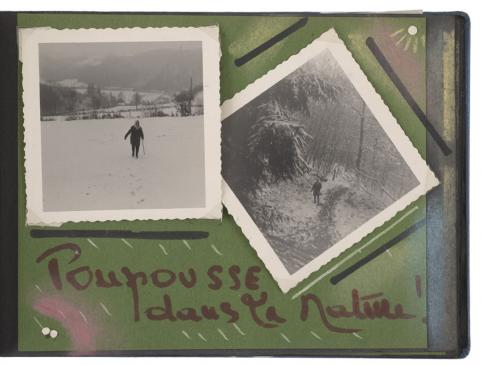

Far from the objectivity it was first claimed to have, photography is the perfect instrument for creating a world that is parallel with reality. When used to serve the ego, it makes it possible to display oneself, to attenuate one’s uglier physical traits, to reinvent one’s life. Once framed, inserted in an album or posted on an internet profile, it reflects what we are prepared to show, what we think looks good. The downside of this ideal is the self-censorship that follows, and in the end the uniform nature of the images, the repetition of stereotypes we thought we were escaping from.

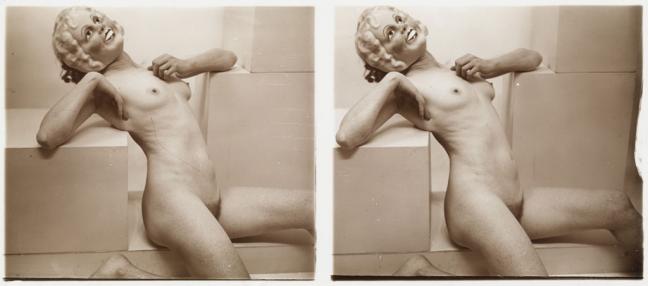

Beyond its capacity for modifying the presentation of reality, photography also has the power to influence our senses and our desires: erotic images, crime scenes… It becomes the privileged influence of our fantasies, prepared to fulfil our passions, feeding universal voyeurism.

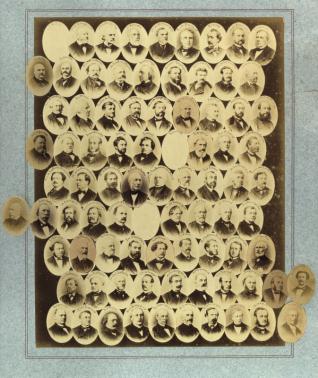

From the beginning, photography was seen as the ideal tool for the worldwide spread of knowledge. The facility in reproducing this mechanical image led people to believe that photographing everything would lead to a global and exhaustive knowledge. But the accumulation of images has had no effect. It shows us things without providing the keys to understanding. Sometimes, for certain photos that have become iconic, it can be limited to idolatry, to the passionate, leaving any possibility of a critical thought as to the subject by the wayside. This utopia of access for all to universal knowledge, despite the mass spread of images from the 19th century onwards and even more with the internet today, remains conditioned on the economic, intellectual and social capacity of each individual.