Curated by

Anne-Marie Filaire

and Sylvain Besson,

musée Nicéphore Niépce

All of the prints for the exhibition were produced in the laboratory at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce on Canson Infinity Baryta Prestige 340g paper.

The museum would like to thank: Canson and La société des Amis du musée Nicéphore Niépce.

Anne-Marie Filaire is not a war reporter who files dispatches from the world’s hotspots. She observes the effects of war, the changes it leads to, the wounds that remain. These are disasters that have cooled off, that cannot be fixed, they must be absorbed and only time can make them fade, but not disappear. Her recent work in Paris and its surrounding regions, happily not exactly at war, most probably needs to be approached from that angle.

Jean-Paul Robert,

D’Architectures, Nov. 2020

Anne-Marie Filaire was 25 years old when she became printer Yvon Le Marlec’s assistant in Paris, a job she held from 1987 to 1991. After getting her technician’s diploma from the Crear laboratory, she immediately went into art printing. Print photography was booming and Le Marlec was one of a select group of well-known printers that every big-name photographer wanted to work with: Dirk Braeckman, Bernard Plossu, Bettina Rheims, Patrick Zachmann… Just like Philippe Salaün or Claudine Sudre, Le Marlec knew how to get the best out of their negatives.

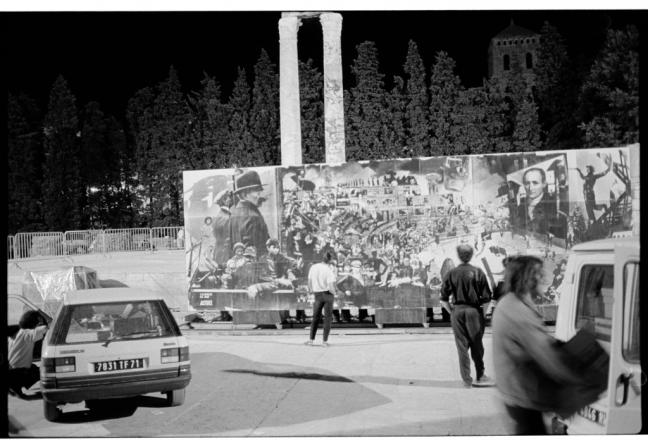

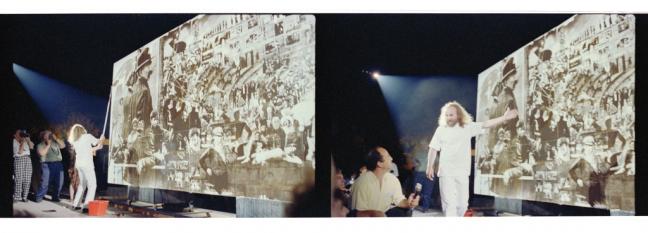

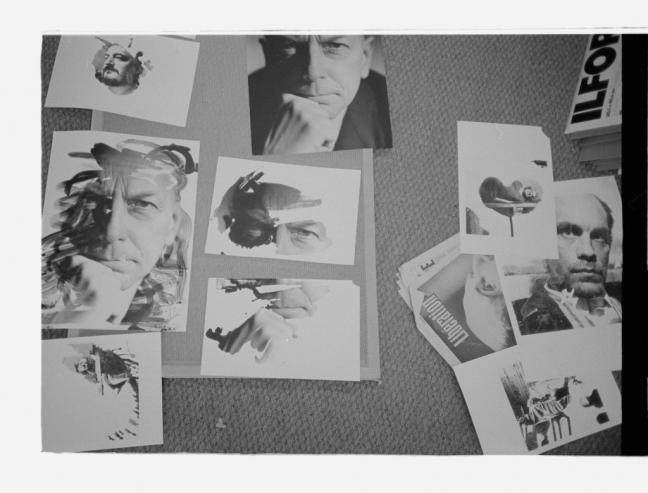

In 1989, Le Marlec had big plans. It had been ten years since he left his job as printer at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce and set up shop in the Rue de Charonne. His ambition was to contribute to the history of photography by inventing a new process. In tandem with the chemist Christophe Bart, they developed a process to develop photographs using daylight. In order to publicise their invention, Le Marlec organised a spectacular show set to music specially composed for the occasion for the closing night of the Rencontres d’Arles. In an old theatre, lit by projectors, he revealed a latent photographic fresco, a giant photomontage (27 panels that measured 1.10 x 1.10m) of extracts from photographic masterworks and portraits of photographers, from Lewis Carroll to Helmut Newton, Bruno Barbey to Edward Weston… The evening was a triumph for Le Marlec who appeared on stage dressed all in white, catching the light, like a guru.

Anne-Marie Filaire worked to assist Yvon Le Marlec during the months-long preparation and manufacturing of the photomontage. She immortalised each instant, revealing the daily goings on of a photographic laboratory, showing every detail until the big reveal on July 8th 1989… Photography was grateful.

The dark room

I arrived in Paris in 1987, and moved into a small top-floor apartment, at 81 rue de Maubeuge in the 10th.

In those days, being a photographer was not really a job. One started out assisting other photographers, in fashion or advertising [I was an intern on a shoot for an ad by Gerhard Vormwald with the famous slogan ‘Ma chemise pour une bière

’ (My shirt for a beer)], for magazines, or as a laboratory technician. There were a lot of labs in Paris, and print photography was big so I chose to go into printing. But I didn’t want to do any old thing, I didn’t want to work in a big lab, I wanted to do art prints.

A well-known printer, Yvon Le Marlec, had just set up shop and was considered to be the best photographic printer in Paris. I had heard about him as I was finishing my photography course.

I was ambitious and determined so I just went to see him with my landscapes of the Auvergne that I had taken and printed myself. I told him I wanted to work with him and he hired me on the spot. So that’s how I started working straight away in Paris, just after I qualified as a lab technician at the Crear. I started working immediately at 5 rue de Charonne with Yvon. To begin with, I did the baths and retouching, until the lab got another enlarger and I started printing. I stayed there until February 1991.

The first photos I ever touched were by Pierre de Fenoyl. At the time, Yvon was working on “Chronophotographies

”, a book published for the Musée de l’Élysée in Lausanne and Charles-Henri Favrod.

Pierre de Fenoyl had just died and I discovered what an impact his death had in the photography world. That was my first physical encounter with a piece. Touching the material, handwashing soaking prints for hours, feeling the paper as it dried, pressing it, letting it stretch, retouching the photos with a brush.

The work I did for those four years was difficult and painstaking. Working in a lab is not easy,

but I was feeding myself intellectually. I met all of the big-name photographers of the day Denis Roche, Bernard Plossu, Antoine Legrand, Bettina Rheims, Xavier Lambours, Paolo Nozolino, Patrick Zachmann, Gladys, Marc Le Méné, Marie-Paule Nègre, Pascal Dolémieux, Agnès Bonnot, Thierry Girard, Ève Morcrette, Claude Dityvon, Jean-Michel Réverdot, Gérard Rondeau, Alain Turpault, Hervé Rabot, Pierre- Olivier Deschamp, Gilles Favier, Claude Bricage, Paul Facchetti… The portraits of Edouard Baldus, the work of Jacques-Henri Lartigue whose I make the preparatory prints for upcoming exhibitions and publications, François Hers and the DATAR Mission photographs. But also those of the magazine Actuel, Claudine Maugendre, Jean-Luc Monterosso, Dominique Gaessler, Pierre Devin, and Claude Gassian, who was on the fringe of the art world at the time. I chose to work with him and I printed the work for the first albums he did for Jean-Jacques Goldman, Renaud, and then for Rock images. The Niépce prize-winners also came from the lab on the rue de Charonne. We also produced the work of foreign photographers who worked all over the world and the developer revealed images by Gabriele Basilico, Sebastiao Salgado, Josef Koudelka, Jeanloup Sieff, Helmut Newton,Robert Mapplethorpe, Marc Trivier…

When André Kertész’archive arrived in Paris in 1987, I was lucky, or privileged enough to look at each of his contact sheets, one by one, to discover part of his work and life. It was, and still is, one of the most moving experiences of photography I have ever had. I have Isabelle Jammes to thank for it, who was working with Pierre Borhan at the time on the publication of Kertész’ “Ma France

”, a book and exhibition for which Yvon Le Marlec produced the prints for the Mission du patrimoine photographique.

I learned everything I know about light and photographic material during those four years. Yvon taught me one really important thing, to know when to stop. I think that is the biggest lesson from my early working life. A photographic print is made from living matter and we are always trying to get the best print possible. We play with chemicals, we look for nuances, depth, light. It can go on forever, and I learned that over the years. At the start I would arrive early, I would prepare the developer according to whatever prints Yvon had to do during the day, varying levels of contrast, according to the paper. I became an expert in dosing hydroquinone, phenidone, sulphite… and I would leave late, having washed, spun and dried all of the prints during the day, to run off to pick my son up from school.

The first exhibition I printed was Lartigue’s “Les femmes

aux cigarette

s”, from glass platenegatives, where one of the faces that appeared was Josephine Baker’s. An entire pantheon opened out in front of me in the dark. My intellect and imagination were nourished by world events and the big changes of the time such as the demonstrations and repression at Tiananmen Square in Beijing. I discovered people from the world of art, literature, the world that I knew from what I was reading, came to life in the floating pictures I handled every day.

At lunchtime, I would go to dance classes at the Café de la Gare. Between two washes, I would go to see films at the Bastille cinema, I remember seeing the Rossellini season from beginning to end. The lab was located at the back of a large courtyard that housed artisans and upholsterers, near Bastille on the corner of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine. I used to sometimes visit the offices of the Cahiers du Cinéma

that were on the Faubourg. At that time, when I was printing other peoples’ work, I was also taking photos, every day with an autofocus L35 Nikon. This exhibition at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce reconstitutes this photographic journal from the busy period when we were working on the fresco for the Rencontres Internationales de la photographie in 1989.

Since 2011, I have been teaching photography at Sciences Po, and I lecture on this period of the history of photography, that I took part in, and that I am still writing today. Photographers from the eighties, were very much part of a tradition, Arago’s announcement of the existence of photography was only 150 years old, we were inspired by the Americans, it was a time of big exhibitions, and when photographybecame part of contemporary art.

Anne-Marie Filaire,

Paris, June 2021

Biography

For over twenty years, Anne-Marie Filaire has been exploring landscapes on regular trips to faraway places, mainly to the Middle-East and Asia. The notion of time is important to her work. Her time frame is frozen, the space of trauma, the blindness of conflict, or even repetition, that she depicts in an extremely constructed and structured fashion She photographs zones where conflict has happened, is happening or is about to happen. Motivated by intimate sparks, far from her family and her home, Anne-Marie Filaire looks for “beauty in light and violence” 1, questioning notions of borders and enclosure, inside territories where history and men have left their trace. While humans are practically absent in her photographs, the stigmata of their passage are omnipresent and the unease is, at times, palpable.

Anne-Marie Filaire’s landscapes are brave and poetic. She never gives in to simplicity, her own stance and subjectivity are key as she explores dangerous regions where it can be risky to be a photographer. By regularly going back to the same places, Anne-Marie Filaire composes an archaeology of these territories. Her process is identical, whether she is photographing landscapes in Auvergne for ten years for the Mission de l’Observatoire Photographique du Paysage or the installation of a wall between Israel and the Palestinian territories: repeated viewpoints, a fascination for the horizon, very structured framing. Her still, silent landscapes bear witness to the passage of time. The true subject of her work turns out to be time itself: photographic layer after photographic layer, the accumulation documents, objectivates but above all, creates a body of work.

Anne-Marie Filaire was born in 1961 in Chamalières (63), and was photograph printer Yvon Le Marlec’s assistant in Paris from 1987 to 1991. Her first, seminal series was created between 1994 and 1996, dedicated to volcanic landscapes in the Puy-de-Dôme and the Cantal (that led to her first personal exhibition at the Musée d’Art et d’Archéologie in Aurillac) set her up as a landscape photographer. In 1999, she began travelling through the Middle- East and Asia, while in France she worked with the Mission de l’Observatoire Photographique National du Paysage. Her work then shifted toward the notion of environments that she depicted through series on doors and bedrooms. She now teaches photography at the Paris Institut d’Études Politiques. Her work has been shown in many exhibitions in France and abroad. The Mucem, in Marseille, held a solo exhibition in 2017 the highlight of which was Zone de sécurité temporaire

(Textuel / Mucem, 2017).

Anne-Marie Filaire continued her exploration through the excavations of the Grand Paris. A number of exhibitions planned for 2022 will showcase this work. In 2020, she published Terres,

sols profonds du Grand Paris

with Éditions Dominique Carré / La Découverte, en 2020.