This exhibition on the initiative of the Nicéphore Niépce museum – Ville de Chalon-sur-Saône, was made possible with the collaboration of the Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation and the Akio Nagasawa (Tokyo) and Jean-Kenta Gauthier (Paris) galleries, and the support of Gacon-Cartier et Camuset, Chalon-sur-Saône, the DRAC Bourgogne Franche-Comté and the Japan Foundation.

Daido Moriyama (born in Japan in 1938) is a major figure in contemporary photography. His contrasted, grainy, cropped, blurred work gave rise to new practices, inspiring a new generation of artists.

The art of Daido Moriyama is founded on the work of Nicéphore Niépce and the roots of photography. In his home, in Japan, he keeps a print of the first ever photograph, Le Point de vue du Gras , framed over his bed, to be able to look at it every day. Moriyama’s devotion to the first ever photograph, has led him to follow the path of the inventor; from Tokyo to Chalon-sur-Saône and Saint-Loup-de-Varennes and as far as Austin, Texas.

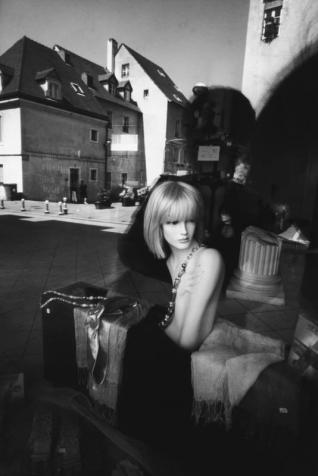

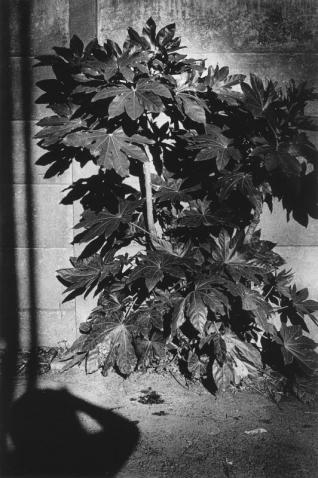

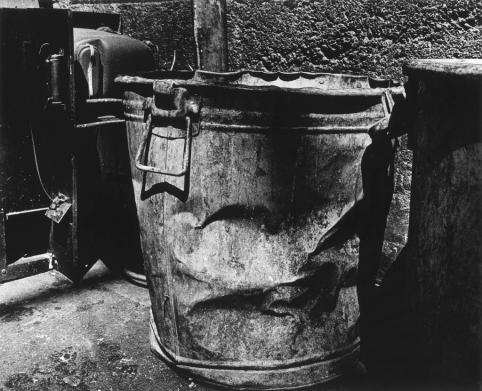

In the eighties in Japan, Daido Moriyama took pictures of everything he saw as he wandered around. Context is but a pretext. He records what he perceives to be the present and the real in the public space that surrounds him, fuelled by the memory of the first ever photograph. “That arabesque of light and shadow, that scene filtered by light soaked into the depths of my memory, just as if I had seen it myself suddenly one summer day. And that scene, bleached by the sun, at that time, at that place, awakens various memories within me, and is suddenly revived in my fingertips as I snap a picture in the present ”. In 1990, he published a selection of these photographs in “Lettre à St Loup”, like a letter through time and space to Nicéphore Niépce. When he was preparing the book, he got the urge to travel to the places where the inventor lived in order to “feel the lights and shadows and soak up the energy of the birthplace of photography ”. This second phase happened later, in 2008, when Daido Moriyama got a chance to explore the places Niépce frequented, including the exact location of the first shot in the “ View from the Laboratory” series . Finally, on a trip to the United States in 2015, he finally saw and photographed the original of Le Point de vue du Gras with his own eyes, in Texas.

The “Daido Moriyama, One summer day” exhibition is the first of its kind. It includes around one hundred photographs that have been brought together for the first time ever. The show is exceptional as it showcases his work on Niépce’s artefacts, in the very museum that is named after him.

In 1816, Nicéphore Niépce started experimenting in photography. His aim was to fix images in a camera obscura, using light. In a letter to his brother dated May 5, he outlined the premise for mechanical pictures: “I put the machine in the room where I work; […] and I saw, on the white paper, the part of the aviary that can be seen from the window, and a light outline of the casement windows that were less well-lit than the objects outside. […] This is still an imperfect trial […] but with work and lots of patience, I think it will amount to something. It happened just as you predicted, the background is black, but the objects are white, […] in fact, it might not be impossible to change the way the colours work .”

In 1827, from the same window, Nicéphore Niépce took Le Point de vue du Gras, which is today considered to be the oldest photograph in existence. It is a tin plate on which he “recorded” the view from his house in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, near Chalon-sur-Saône.

Daido Moriyama was born near Osaka in 1938 and got into photography after studying graphics. He moved to Tokyo in the early sixties, starting off as an assistant to big-name photographers such as Shomei Tomatsu and Eikoh Hosoe, and by the end of the decade had become one of the leaders of the avant-garde movement Provoke ; the name of the photography magazine that published the best of contemporary Japanese photography. He made a name for himself straight away with his monograph Japan , a Photo Theater, which was published in 1968. It was to be the first in a long line of photography books (almost 200 to date).

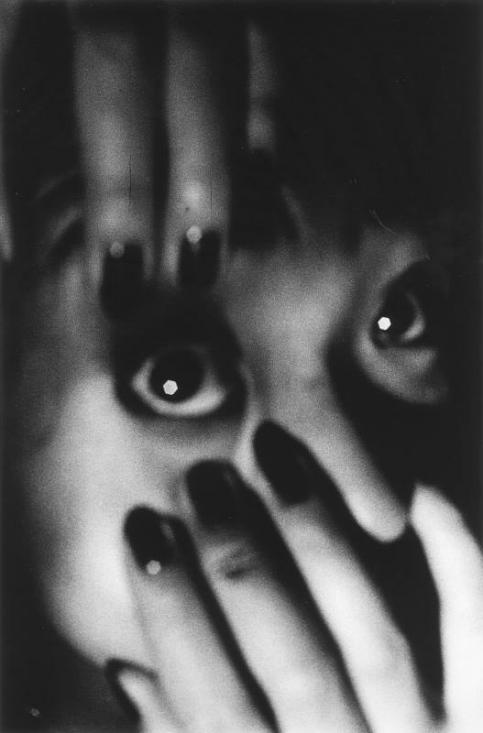

He takes black and white, hugely contrasted, grainy shots with no legend, using non-conformist techniques. His graphic prints, with no text and his immersive installations were to mark the world of photography. He invented a new language that heralded a new era for street photography.

At first glance, Nicéphore Niépce’s work and that of Daido Moriyama seem to be very different. But when we take a closer look at the photographs and delve into the artist’s writings, the influence is obvious.

Nicéphore Niépce’s Le Point de vue du Gras is a personal view of the outside world. It is imbued with the time it took to record the light (it took Nicéphore Niépce eight hours to get a result). At first glance, the photographic landscape appears enigmatic, in particular as the black and white reproduction is the only image that appears in photography history books. It is blurred, extremely grainy, and with very distinct areas of shadow and light. All of these descriptive features are also obvious in Daido Moriyama’s work. In addition to this similarity of form, the artist and the inventor also have similar approaches to their work. One of the driving principles behind Nicéphore Niépce’s invention was that pictures should be copied and shared. Publishing is of the utmost importance to Daido Moriyama, his idea of photography is dominated by the importance of the multiple, printed image.

Since his career began, Daido Moriyama has been haunted by Nicéphore Niépce’s first ever photograph. He writes: “This photograph reminds me every day that we must never forget the origins and essence of photography, and the very existence of dark and light”

In his autobiographical book, “Memories of a Dog” published in 1984, he wrote: “Following my eye’s memory, all the way into the past, the scene of a distant summer day comes alive on the far side of receding time. Probably a view of a back garden seen through a window, what appear to be a house and trees are burned into an asphalt plate. They have lost most of their contour, light and shadow flying past each other in a rough blur, an image that is just like a fossil. This one scene of a summer day presented itself exactly 157 years ago before Nicéphore Niépce, a scientist living in Saint-Lou, in the remote countryside of France. The scene became the world’s first “photograph”. Of course, there’s no way I could have witnessed that scene myself; I encountered it for the first time in a photography book some ten-odd years ago.”

The photographs from 1980 published in the book “Lettre à St Loup” in 1990, are for Daido Moriyama “a recollection of the sacred landscape of Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, and a personal tribute to Nicéphore Niépce, without whom, there would be no photography in the world .”

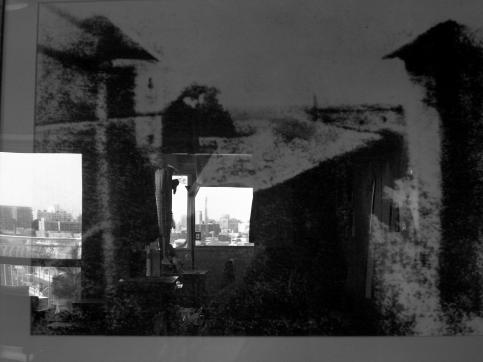

On a 2008 trip to Bourgogne, he went on a pilgrimage on the trail of the inventor. First, he visited Chalon-sur-Saône, the house Niépce was born in, his statue, the work preserved in the museum, and his camera. Then, he went to Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, where there is a monument to Niépce, and finally, he went to his house.

“As soon as I found myself faced with this view [Saint-Loup-de-Varennes], the image of shadow and light from Niépce’s iconic photograph started to replace the real landscape in front of my eyes and suddenly, I had the feeling that I could see through Niépce’s eyes.”

The photographs he took on this journey were a way of connecting with the inventor, a means to validate his existence as a photographer.

Daido Moriyama put the final touch to this personal, creative journey in 2015. He took advantage of a trip to the United States to go see Le Point de vue du Gras “with his own eyes”. The photograph, which is part of the collections at the Harry Ransom Center, at the University of Texas in Austin, is difficult to observe. There is a reflection from the tin plate and the contours of the objects are almost invisible. But this mattered little to the photographer; after all, the image is already indelibly etched in his memory.