Photography, for Klavdij Sluban is a pretext for travelling, for experiences and encounters, and gaining a better understanding of each person’s reality. The Slovenian photographer bears witness to what he sees, not to what he should have seen. He eschews the anecdotal, relates no events, remains outside the current, and doesn’t hesitate to capture the in-between times when nothing is happening. In the four corners of the earth, he harnesses the atmosphere of a city, the darkness of a jail, the solitude of an island. An often chaotic world where man is never far away. Klavdij Sluban’s work appears to be located out of time on purpose. The charcoal aspect of his grainy prints and his commitment to black and white are part of the beauty. The photographer’s sensibility is in symbiosis with the reality of the world.

This exhibition is the photographer’s first retrospective, showcasing twenty years of work that is already present in the most prestigious of international collections.

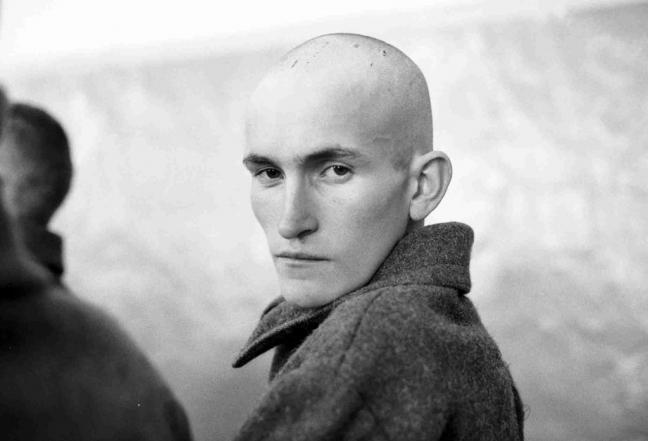

A train compartment, a prison and an island, Klavdij Sluban’s encounters with human destiny happen in enclosed places. These spaces produce feelings of solitude, boredom and at times, terror. Following a continuous path, and a steady moral compass, Klavdij Sluban heads into regions that have been abandoned by God. The trip itself holds no interest. There is no such thing as time either. There are only portraits of men and women suffering as he does. Haggard in the face of history, each face is an interrogation, a question asked of destiny. Photography aims to be radically out of time but nevertheless it is located in the very greasy and charcoal matter of facts. It states and presses. Each image gives us a glimpse of catastrophe. Through the windows of the train, behind the security glass, we can only see greyness and the impossibility of living. Simply.

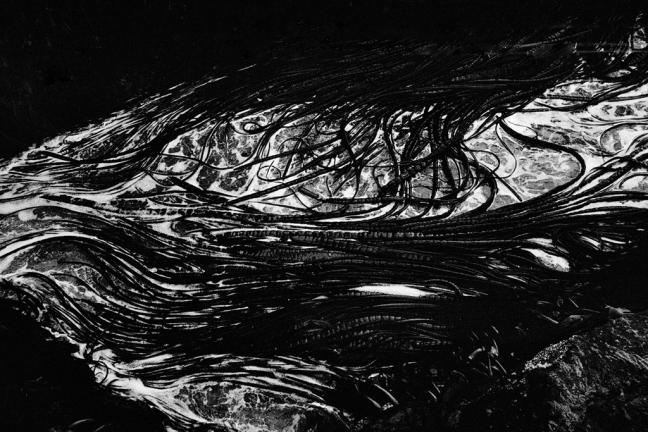

At times, in Cuba, in Haiti, the bodies revolt and refuse the diagnosis. Beauty, as it still exists in this unhappiness, remains a necessity. The corpse-like beauty of a young inmate, of a profile, glimpsed in Siberia, of an old lady in a bus, the form it takes is that of melancholy. The photographer is not a documentarian neither is he an “auteur”. He takes no part in the debates that animate the photographic world. The only noise that comes from his images is that of the cold wind or the swell of the sea. Here, things are silent. Talk is scarce. And confessions are even scarcer. In this world without complaint or recriminations, in this obscure state, the narrative is short. That’s just the way it is, there’s no point.

But this narrative is never direct. Between the real and the photographer there is a pane of glass, a window, a tear, and always a lens. Before embarking on a voyage, Klavdij Sluban already knows what he will find and feel. Back to square one, the second he crosses the border, walks into the prison, he is plunged into a world he knows, without contrast. Life is not the confusing and contradictory puzzle presented to us. It takes on the tragic and literary form of a dying animal, of predestined lives.

He has seen too many condemned inmates, heard too many sentences for photography to be the subject of controversy. We could say however that photography, as practiced by Klavdij Sluban, is paradoxically made up of sensuality, sadness and severity.

But we never feel like fleeing these images. It is as if we are being presented with a vision of our own conscience. Something gets us by the throat; a face to face with child inmates, the greyness of the city, the sparse landscape of an east European country. But it’s still beautiful! We can’t find any other adjective to describe these photos. And we are not talking about the type of beauty that makes the pain of the world look good! This is an extreme beauty that reflects nobility and reveals to us the tragedy of our existence.

So we need to see three sequences, the train, the prison and the island, as the same film that provides us with a Passion without Christ, a world in thrall to stronger forces. We are left with the stoical, overall image of an unanswered question and above all the obstinate will to link beauty to melancholy.

This body of work, patiently built over twenty years, is shown without illusions. The time is gone when one photo alone was enough to open eyes and consciences. In fact, that time never existed. But what makes these remarkably few images so powerful is this feeling of powerlessness that is far from resignation. This immobility is nothing less than a monument erected to our condition.

François Cheval